UDC: 781.7(6)

78:316.7

COBISS.SR-ID 59552009 CIP - 4

_________________

Received: Jan 5, 2022

Reviewed: Jan 24, 2022

Accepted: Feb 02, 2022

#1

ANATOMY OF ETHOS, PATHOS IN MUSIC OF AFRICA

AND ITS PATHOGENIC ESSENCE

Charales O. Aluede

Department of Theatre and Media Arts,

Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria

[email protected]

Olatubosun S. Adekogbe

Department of Music

Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria

[email protected]

Department of Theatre and Media Arts,

Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria

[email protected]

Olatubosun S. Adekogbe

Department of Music

Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria

[email protected]

|

Citation: Aluede, Charles O. and Olatubosun S. Adekogbe. 2022. "Anatomy of Ethos, Pathos in Music of Africa and its Pathogenic Essence." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 7:1

|

ABSTRACT

There is the need to re-examine what was previously held as age-old truths in the light of new findings; the issue of music and its use in our contemporary societies is one of such. For example, there was a general assumption that music making has no side effects and that everyone enjoys music. Today, musicogenic epilepsy stares at our faces and we have come to know that such beliefs are not truly so. Without contradiction, music features in major activities in our daily living. The avenues for music making in traditional societies are gradually being taken over by the churches, club houses, social and cultural organisations with high wattage of volumes. This development has some negative effects on human and environmental health. This study uses a descriptive research method which entails quantitative and qualitative designs. Data were elicited through participant observation, interviews, review of apt literature and questionnaires. A4D Tuner, a tool for measuring sound pressure levels was used to assess the volume of sounds often emitted in certain social and other gatherings. It was observed that most of the musical avenues visited emit sounds which are far above the recommended 75dB as stipulated by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The work predicts that bathing people or the environment with excessively high volume of sounds will in no time engender physical and emotional disturbances, neural deafness and even total deafness. Consequently, it suggests that the government should make adequate legislation on sound pollution to arrest this malaise.

Keywords: anatomy, ethos, pathos, pathogens, public health, music therapy |

INTRODUCTION

Although no one can talk with exactitude, the origin of music, everyone enjoys music making and its concomitant attributes. How music evolved and the actual age of music is not too clear. For an instance, McClellan (2000) observes that in the world’s mythologies, music was either discovered or was bestowed on us by supernatural beings. Henry Farmer in McClellan (2000) further opines that:

the earliest physical evidence of musical activity that we possess, a clay ocarina with five holes, bespeaks an already flourishing music as early as 10,000 B.C. whereas our emergence as specie has been dated to at least one thousand years ago. So too, our earliest civilization has been estimated to have been established no more than 8,000 years ago, yet within them we find evidence of an already flourishing culture where music occupied a well-regulated position in social and religious life of its people. (McClellan 2000, 1) These gaps notwithstanding, it is generally a known fact that music serves a lot of positive roles in the lives of humans. For example, within the African soundscape, music is known to be made from infancy through adulthood to death. Today, there is a growing need to take a second look at the use of music in our daily activities. No doubt, while the avenues for music making in our traditional societies are waning, contrastingly, music making in the churches, club houses, social/ cultural organisations, and schools is waxing. That the composition of these ensembles' membership is compromised is to say the least. This fundamental compromise begets the kind of music, choice of musical instruments and volume of sound production we are bathed with on a daily basis. These tendencies have their attendant negative effects. Since music is a powerful tool which works on our emotions, and since our emotions have the propensity of controlling our overall well-being, it has become exigent to undertake a seminal study on the pathogenic stance of music in today’s world.

Definition of selected terms

Quite relevant to this paper are three major terms which are considered crucial to be properly defined within the context of the work. This is reasoned vital as it would give us a smooth transition into every segment of this research. From the etymological point of view, Ethos is a Greek word meaning "character" that is used to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize a community, nation, or ideology. The Greeks also used this word to refer to the power of music to influence emotions, behaviours, and even morals [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethos]. It is within the latter cusp that we intend to dwell much on. Therefore, to talk about musical ethos, we are without doubt, concerned about the characteristic features, attributes and fundamental values of music as part of any given culture. In a similar vein, Singer (2013, 209) opines that Pathos plural: pathea or pathê is from a Greek word which means "suffering" or "experience" or "something that one undergoes," or "something that happens to one". Put quite simply, the British online English dictionary defines pathos as the quality or property of anything which touches the feelings or excites the emotions and passions, especially that which awakens the tender emotions, such as pity, sorrow etc. Although of Greek origin, in contemporary parlance, pathos enjoys a kind of duality in arts and medicine. While in arts it is said to touch feelings or excite emotions, according to Singer (2013, 209) Pathos in medicine refers to a "failing," "illness", or "complaint." Stopper (2021), puts it succinctly that Patho, a prefix derived from the Greek "pathos" meaning "suffering or disease, serves as a prefix for many terms including pathogen (disease agent), pathogenesis (development of disease), pathology (study of disease), etc.

Materials and methods

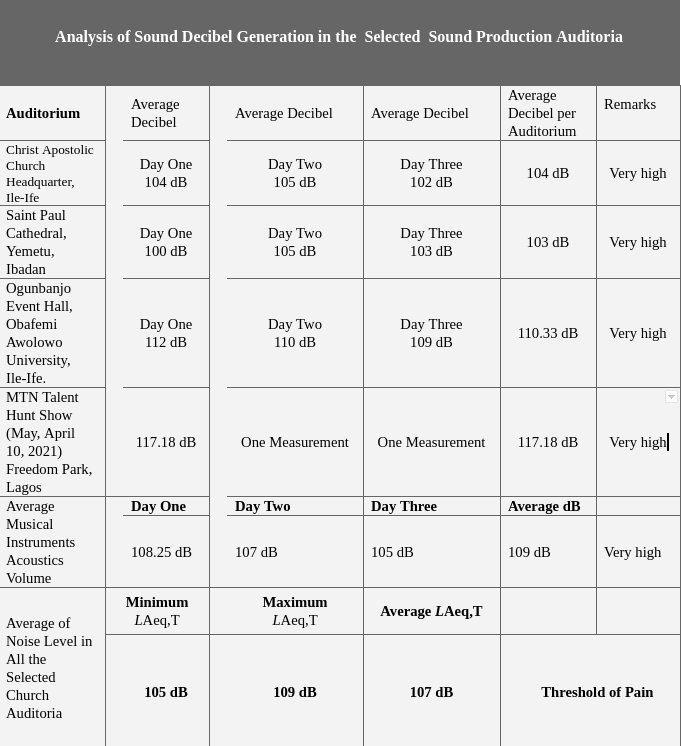

To elicit the relevant and related data which is required in this study, we relied on descriptive research method. This method combines quantitative and qualitative designs. Much attention was given to participant observation in churches, social ceremonies, concerts and club houses. Interviews were conducted and a review of apt literature was done. A4D Tuner, a tool for measuring sound pressure levels was used to assess the volume of sounds often emitted in some selected churches and other social gatherings. These methods of data extraction were enhanced by the use of questionnaires to obtain robust information needed for an encompassing gaze at the Nigerian soundscape.

Music in human life

Though a subject of debate as to when music making began, there are somewhat sacrosanct opinions about music itself and how/when humans get to know musical impulses. There is overwhelming evidence that human beings who are biologically created have had music as part of their creation even before birth. For example, in the opinion of Levitin (2007): Inside the womb, surrounded by amniotic fluid, the foetus hears sounds. It hears the heartbeat of its mother, at times speeding up, at other times slowing down. And the foetus hears music, as was recently discovered by Alexandria Lamont of Keele University in the UK. She found that, a year after they are born, children recognise and prefer music they were exposed to in the womb. (Levitin 2007, 222) Levitin is not alone in the position cited above. Parncutt (2016, 220) reports that the acoustical stimulation to which the foetus is exposed to is more diverse and carries more information relative to corresponding discriminatory abilities than visual, tactile or gustatory (biochemical) stimulation. Reporting an earlier investigation, the author opines that “the foetus hears throughout the second half of gestation because, the foetal inner ear is filled with fluid, much of the sound heard by the foetus is transmitted through the skull by bone conduction.” Corroborating this fact was the narration of my wife during the pregnancy of our first child that the baby dances to music in the foetus. This was also confirmed by a Nursing Matron Mrs. Fatuloju of the Anti-Natal Clinic of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife in an interactive interview on May 27, 2021 at the Hospital premises.

Recapitulation

In this segment, we intend to present kaleidoscopic snapshots of resources on music and humans in the last two decades. A terse reprise of previous beliefs by some scholars about the use of music to bring about healing is considered necessary here as this will provide the much needed pivot to latch into the nexus of this study. Within the last two decades, quite a number of voices have attested to the therapeutic potency of music. Cottrell (2000) remarks that: Since the beginning of recorded history, music has played a significant role in the healing of our world. Music and healing were communal activities that were natural to everyone. In ancient Greece, Apollo was both god of music and medicine. Ancient Greeks said, ‘music is an art imbued with the power to penetrate into the very depths of the soul’. These beliefs were shared through their doctrine of Ethos. In the mystery school of Egypt and Greece, healing and sound were considered a highly developed sacred science. Pythagoras, one of the wise teachers of ancient Greece, knew how to work with sound. He taught his students how certain musical chords and melodies produce definite responses within the human organism. He demonstrated that the right sequence of sounds, played musically on an instrument, could actually change the behaviour patterns and accelerate the healing process. (Cottrell 2000, 1) The healing power of music has been recorded as far back as 1500 BC on Egyptian medical papyri (O’Kelly 2002). More recently, there has been a resurgence of music in healthcare brought about by music therapists (Hogan 2003). Furthermore, music has been used for improving physical, psychological and emotional problems during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Europe (Cardozo 2004). The healing powers arising from the mystical intercourse of music and prayer have captured the attention of prophets and poets, scientists and physicians, the lay and the learned alike throughout the ages and across the world. In the present global-cultural milieu, where professional, affordable healthcare is scarce at best for the majority of humanity, where a staggering number of people in the wealthiest country of the world are without basic health insurance, where medical mistakes have become far too numerous, and where an increasing number of individuals are opting for ICAM (integrative, complementary, and alternative medicine) approaches to health care, much can be learned from cultures that have ancient traditions of ICAM healing (Koen,2009, 1). These opinions tend to give much credence to the healing forces of music and a need for an integrative mechanism which will include music and other related arts. In this thinking, Daveson, O’Callaghan and Grocke (2008, 280-281) have identified indigenous music therapy as a platform which encapsulates the roles of the music therapist, the client and the philosophy behind the activity. Music and healthcare have been interconnected from the time of the ancient Greeks (Gallagher 2011). According to Stevens (2012): Much of the world is singing, dancing and drumming with little concern about whether they have talent or will become famous. Music is woven into the fabric of life in many music cultures; it is an essential medicine for creating joy, gathering community, generating hope, freeing the spirit, communing with the spirit and educating the children. (Stevens 2012, 3)

This practice is a common phenomenon in Nigerian societies where there are many avenues for music making and to contain excesses, some genres are regulated by traditional modes of music censorship. That music is a powerful invention which man is constantly exploring is not to be doubted. Its powers have been acclaimed by quite a lot of people and also aptly captured in literature. The views of Koen et al. (2012), and Hanser (2016) are shared below. According to Koen, Barz and Brummel-Smith (2012):

Music is as diverse as the number of people who exist. Throughout history, the potential transformational power of music and related practices has been central to cultures across the planets, and music has been far more than a tool for evoking the relaxation response. It has been a context for and vehicle for expressing the most deeply embedded beliefs and expression of human life and a way to create or recreate a balanced and healthy state of being within individuals, families, and societies. (Koen, Barz and Brummel-Smith 2012, 12) This claim is further corroborated when it is said that: Music immerses us in the range of feelings that guides self-discovery along the path to healing. It also anchors us, as we grasp the meaning of music in our lives and create new ways of expressing ourselves. While we access, explore, and communicate the deluge of emotions that can flood us when we are ill, it is possible to become well, even if we are not healthy. Music therapy empowers us to embark on a sacred quest to find the healer within, and come to peace with our physical conditions and their psycho-spiritual concomitants. (Hanser 2016) In recent times, music as a field of study has become enlarged. Thus remarks Ticker (2017) that: [ ... ] fields such as music therapy has been expanding and growing. Clinicians are using music in therapeutic settings to help those with brain damage or developmental disorders, especially in regard to children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and patients with traumatic brain injuries. Music is very powerful, and its effects on brain plasticity, cognition, emotion, and physical health have important and valuable repercussions for the field of healthcare. (Ticker 2017, 1) So far, not much is heard of the negative effect of music making and listening. This palpable silence needs a proper re-examination. The positive attributes of music have been over-flung to the degree of a total brainwash such that there is a general assumption that constant and unchecked music making is advisable. Even in recent times, we still hear that according to O’Connor (2020, 1) music stimulates the brain centres that register reward and pleasure, which is why listening to a favourite song can make you happy. There is in fact no single musical centre in the brain, but rather multiple brain networks that analyse music when it plays, thereby giving music the power to influence everything from our mood to memory. Humans and Musicing: The need for Caution

That mothers throughout the world and as far back as in time as we can imagine, have used soft singing to soothe their babies to sleep, or to distract them from something that has made them cry (Levitin 2006, 9), and that synchronised singing and dancing did more than just facilitate the building of large- scale civic structures and helped build political structures as well (Levitin 2010), is not sufficient to undermine its side effects.

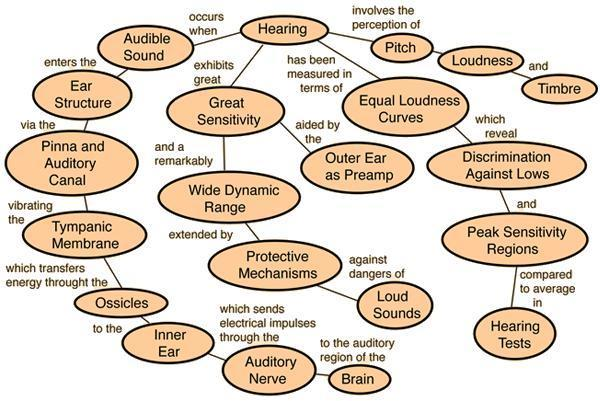

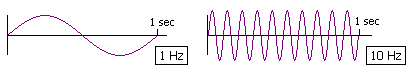

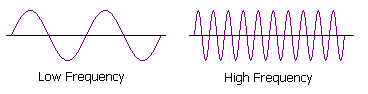

Early in time, a word of caution was given by Benson (2010, 18), when he observed that not all music has the potential to be healing music. There is rare epilepsy called ‘musicogenic epilepsy’, which is induced by listening to music played by an orchestra, even the sound of the piano or ringing bells can cause an attack on human health if played at an excessive volume that can cause ripples in the human ear. Complementing the effects of high volume of sound on the human ear, Benade (1990, 532) opines that sounds are perceived through hearing, hearing is achieved through the ear and the ear has a threshold of what volume of sound it can accommodate. Any sound beyond what the threshold of the human ear can take is considered as noise. Any sound beyond what the threshold of the human ear can take is considered as noise. In another subject relating to the perception of musical sound, Smith (1997) observes that sound perception in terms of combination of tones, when two tones that are close together in frequency are sounded at the same time, beats generally are heard at a rate that is equal to their frequency difference. In other words, when the frequency difference exceeds 15 Hz, the beat sensation disappears and musical tone roughness appears and this is when musical sound turns to noise. (Smith 1997, 228) Schaeffer (1991, 266) discovers that the sound processing performed by the ear and the brain is extremely complex, and difficult because it involves subjectivity of hearing, listening, understanding, comprehension of musical sounds. Sound level measurement in church auditoria has to do with sound pressure level (SPL) which can only be determined by use of Sound Meter Reader (SMR) that is commonly used, as postulated by Krug (1993, 25) in the measurement of noise pollution research or investigation that reading from a sound meter does not ascertain the possibilities of accurate facts on how sound is perceived by individual because perception of sound is subjective especially in Africa where sound is arrogated to power and affluence. Adesiya (2005, 42) also argues that if two individuals engage in an argument, the public always has the notion that the higher voice between the two is winning the argument. Objectively, at sixty decibels (60dB), the loudness of sound is still perceivable as approved by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Nagata (2001, 38) posits that in a church auditorium, the perceived sound consists of directly primary radiated sound from the source and reflected sound various surfaces of the hall especially, walls and ceiling. This reflected musical sound is usually confused for reverberation because, the perceived sound consists of both primary and reflected sounds. In this connection, McAdam & Bregman (1979, 28) posit that the primary sound determines the perceived volume level because this is appreciably louder in the sense that sound becomes softer in proportion to the square of the distance traveled and the reflected sound travels a much longer distance, and sound is partly absorbed and diffused by the reflecting surface. Arising from the above argument, it is opined that all reflected sounds normally play an insignificant position in the real pick out volume level. Thèberge (1999, 69) complements this by stating that primary sound and reflected sound are essentially two separately arriving sounds of different volume levels. In other words, this could be regarded as fundamental and residual musical sounds. Commenting on another characteristic of hearing, Rosch (1978, 548) writes that the combined sounds are perceived as being only as loud as the volume of the two sound-sources. The louder sound determines the apparent volume level; the lower sound does not add appreciably to the perceived volume level. Our daily experience of musical sound perception has put it that larger part of the sound-producing environments are full of sound reflecting materials and substances because one or two of these objects are usually closer to the sound source and that the reflecting surfaces are proportionally much farther away as far as our understanding can guide us. Therefore, this has conditioned our ears to hear but could not distinguish between the fundamental and the harmonics sound where the volume of the reflected sound has some lower decibels than the primary sound. The obvious interaction of the volume of the precise and non-precise musical sound require preservation in order to make musical instruments acoustics in church auditoria natural. The flowing order of sound measurement level as propounded by Georg von Bekessy (1938, 152) using the Place Theory of Sound Perception (PTSP) is seen in Figure 1.

Measurement of sound pressure level (SPL) requires sound metre readers such as A4 DaTuner in order to provide accurate percentage of produced sound and sound received in connection to the sound producing environment like a worship auditorium. This is a digital process to assist in plotting a graphical explanation of sound intensity, sound frequency and sound decibel.

Concept of Loudness of Musical

|

References

|

This website is under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD