UDC: 784.68:393.7(669.1)

78:316.7

COBISS.SR-ID 59576585 CIP - 5

_________________

Received: Jan 13, 2022

Reviewed: Jan 28, 2022

Accepted: Feb 05, 2022

#3

AN EXCURSION INTO THE ROLE OF MUSIC IN COPING WITH

BEREAVEMENT IN ESAN, EDO STATE OF NIGERIA

|

Citation: Aluede, Charles 0. 2022. "An Excursion into the Role of Music in Coping with Bereavement in Esan, Edo State Of Nigeria." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 7:3

|

Abstract

There is a plethora of proverbs and songs in Esan traditional society which are connected with issues related to death and dying. Some of such apt proverbs are that: death knows no king, death does not know a scanty village to spare, one cannot be sick to the extent of not being able to die, death is no respecter of anybody, death is no problem but it is sickness which is the great destroyer, everything done early in life is good except death, death spoils all things; when death comes, one cannot say one is not ready or death cannot be lobbied to spare one for a while to mention but a few. These opinions held by the people are not only spoken but crafted into songs. That the people have a stupendous collection of songs and proverbs themed around death is indicative of the fact that death itself is a -well –thought- of phenomenon in their cosmology. To elicit data for this study, a mixture of research methods was used and these included library search for relevant literature, interviews and active spectatorship and observation. The study presents some notated dirges and does their textual analysis to reveal the people’s construct of death and evaluate the therapeutic potency of their song texts. In the course of this investigation, it was discovered that because death reeks much displeasure in the forms of guilt feeling, emptiness, insecurity, and sadness, elegies are never rehearsed but are performed as soon as a kinsperson dies. Consequently, it was observed that the profuse performance of dirges among the Esan is to strengthen those left behind physically, emotionally and spiritually. It is our thinking that this work will be a contribution to the growing body of knowledge in Thanatology, as well as studies relating to the mournful piece of music, intended to accompany funeral or memorial rites, as a memorial to a dead person, in contemporary discourses.

Keywords: Grief, Bereavement, Therapy, Death, indigenous knowledge, funeral dirge, Thanatology, Esan Introduction

|

Methods and Materials

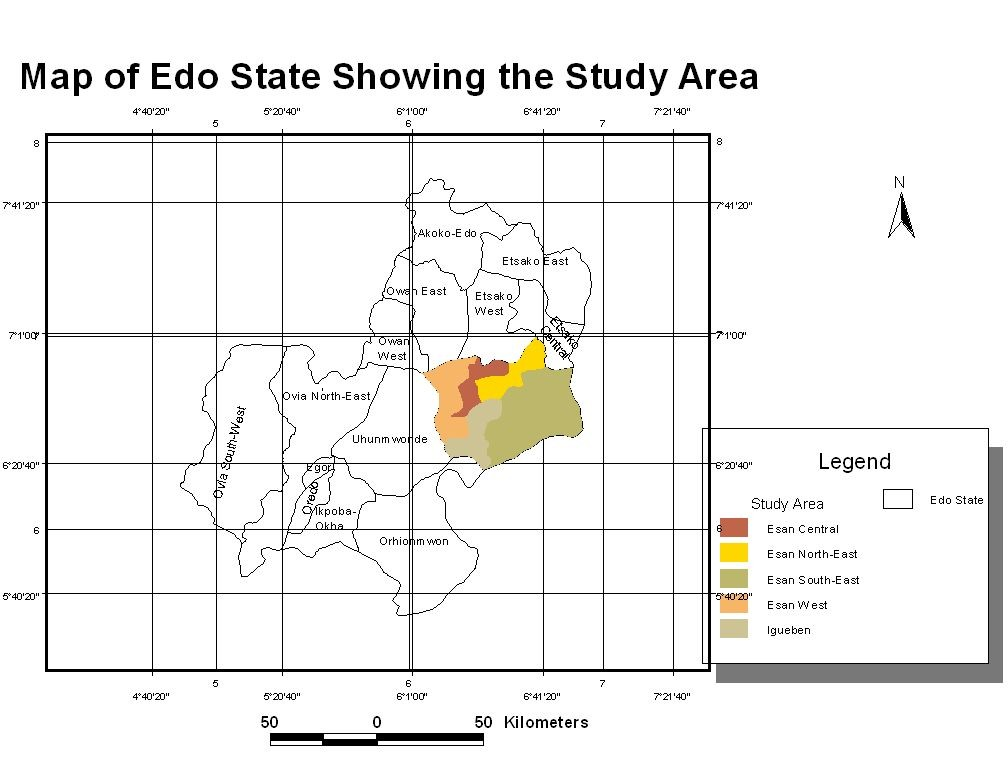

In this article, we relied on ethnographic method of inquiry to elicit data and provide answers to the myriads of questions raised in this work. To be able to do so effectively, we adopted a mixture of styles to mop up information some of which are: (a) Literature search, (b) Interview and (c) observational technique. Esanland is grouped under five local government areas for administrative convenience. These local government areas have Ubiaja, Uromi, Irrua, Ekpoma and Igueben as administrative headquarters. Semi-structured interviews were conducted and data were elicited from fifty-five (55) respondents out of whom thirty were elders, five were trained medical doctors (one each from the five local government areas) and the others are young and old adults. Semi-structured interviews were conducted and data were elicited and analysed accordingly.

Kinds of Death in Esan Worldview

Here, we would like to start by examining briefly kinds of death from Esan lens. Among this people, death is not just taken in as its name implies. The variables responsible for death are often given a due consideration too. This consideration has a link with the expected funeral observances. Aluede and Aluede (2012) have interrogated this subject matter a great deal and we would like to cite them here elaborately. To them, death could be shameful or glorious. To die of poverty, hunger, neglect or to be discovered dead as a result of foul odour perceived from a decomposing body obviously are no news of good tidings. Similarly, to die through self-help (suicide) or going against community mores as in dying in the bush and dying of mental disorder in the community are also strands of shameful deaths. While in Esan vocabulary Uumhin-oya implies shameful death, Uumhin-eghonghon means joyous or glorious death. Dying peacefully in a sleep, dying after a very brief illness and not dying of protracted and malignant ailment that could dry up available resources at an old age is regarded as joyous or glorious death. Aluede and Aluede (2011) are not alone in this thinking. It is in this connection that Izibili (2017) opines that

Death to the traditional Esan people, is of two kinds. The first they refer to as “Good death” Good death is that which takes place when the person has attained a reasonable age and the children are grown up to give him a befitting burial. “Bad death” is such that happens when an under aged dies right in the very eyes of the parents… Another kind of “bad death” is suicide (Uhoa). (Izibili 2017, 83-84) Uhoa is different from Uhohoa. Uhohoa is to go with the wind and wonder to an unknown destination. In Esan, death is subject to scrutiny and it is this scrutiny that determines the kind of interment that the deceased gets. (Aluede 2019) Death in Esan Worldview

In Esan belief and perhaps in many other Nigerian ethnic groups, death remains a major puzzle to all mortals. There are three major miseries relating to death; they are how, where and when one will die.... Even when someone dies as an octogenarian or nonagenarian, death is still seen as a sudden development (Aluede and Aluede 2011, 12). There are proverbs in Esan which attest to the fact that death as the ultimate terminator of humans is of concern to all irrespective of their political, religious or economic status. Some of them are: Sade ai len emhiamhen no da gbo okhomhon, a re toto ruen (If it were possible to know the ailment that will kill a patient, one would have responded swiftly), death knows no king, death does not know a scanty village to spare, one cannot be sick to the extent of not being able to die, death is no respecter of anybody, death is no problem but it is sickness who is the great destroyer, everything done early in life is good except death, death spoils all things; when death comes, one cannot say one is not ready or death cannot be lobbied to spare one for a while to mention but a few. It is this thought process that has made Esan people to put mechanisms in place in arresting and coping with the tension, shock and grief associated with bereavement.

Coping Strategies as a result of Bereavement in Esan

The realisation that death has taken away one’s beloved is of grave botheration. This realisation threatens both young and old in similar and different ways. For example, while talking of kids and death, Lathom-Radocy (2002) observed that:

It is normal for a child to feel sad and upset after a death in the family, the loss of a favourite pet, or a loss of a friend. Symptoms similar to depression may occur: Irritability, poor concentration, changes in sleeping and eating habits, and social withdrawal. The child may also experience separation anxiety, especially if a parent has died and there is fear of other caregivers not being available for him or her. (Lathom-Radocy 2002, 74)

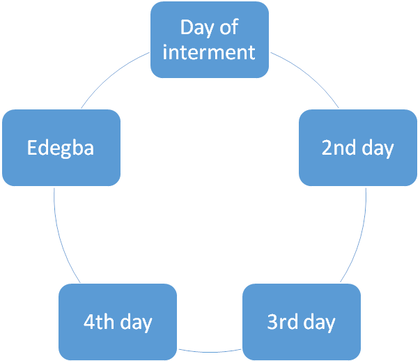

From the Esan indigenous knowledge it is an already known fact that when death has occurred in the neighbourhood, mutuality is threatened. Myriads of thoughts and questions often plague the mind of the bereaved. Musical intervention is required to stabilise the bereaved. To them, music may heal singularly or with some forms of psychotherapy, rituals and prayers. A major example of such circumstance is during bereavement. On such occasions, music is primarily used in dealing with emotion borne cases like grief, sadness, anger, anxiety and bereavement. Bereavement resulting from loss of a dear person is usually the precursor of grief and sadness (Aluede 2010). Williams (1995) talked specifically of bereavement related illness when he opined that: When we lose a loved one through death, we may normally and naturally deny our deep loss for a time. Yet if this denial continues and we suppress the reality of this death, we may become ill and need help. (Williams 1995, 10) Death of a beloved one is often greeted with much denial in the forms of soliloquy or spoken words like: “It is not possible”; “I do not believe it” or “I won’t believe it”. And at some points, it graduates to “Why me?”, “Am I the only one in this community?”, “Could this be happening to me again?”, or “Lord, where are you?” These thoughts are not only mind perturbing but pathogenic. To arrest such thoughts within the minds of the bereaved in Esanland, a circle of uninterrupted music making in the home of the departed is normally instituted as soon as death occurs. For an uninformed spectator at the traditional funeral of an Esan person, the observances in the forms of rites, chants and musical performances are enough to conclude that too many human and material resources are wasted in the exercise. However, taking a second look at the essence of such activities, one would pause to learn from the indigenous knowledge systems of the people in enhancing contemporary lifestyles. There is a philosophical basis for the five days circle of every evening rendition of dirges among these people. This principle is contingent on their theory of Ene ka mie emin bhe ‘gbe, ei jie ne kike mien da hoa (Those who first experienced calamity do not allow those experiencing it lately to commit suicide). This formula is akin to Kapanga which is a music healing tradition in Western Kenya – an institutionalized music which is usually performed for women at the point of delivery. These women in labour are treated to a performance of special music by fruitful women in the community to help them reduce the traumatic experience associated with childbirth. Music is made to midwife women in labour to safe delivery (Mulindi-King 1990). In most Esan communities, funerals often start with Ujie performances. Ujie has an exclusive place in the rites of passage of the dead in Esan. Aluede and Aluede (2011) observe that during the Ujie performance, the children, siblings and friends of the departed are able to hi in respect of the dead. To hi for the dead is to say some chants, recitatives or even songs in praise and prayer for the deceased. Where the challenges that befell the dead are known to some family members, the chanter prays against all of them in the dead person’s next earthly life. Iganede or Ilede in Esan means ‘wake keep’. In times of bereavement, as soon as the departed is buried in the late afternoon, family members and friends gather in the deceased’s home with simple musical instruments such as the bell, gourd rattle, samba, thumb piano, etc., to keep the night with immediate family of the departed. Prescribed dirges are performed for a circle of five days starting from every evening to midnight. The five days start counting from the day of interment. In this area, they actually consider a week from the traditional ritual calendar of five market days which is Uhen and Usumun as two circles of market days - and a month is considered from the perspective of lunar months. Although today these traditional styles of calculations have given ways to modern seven days in a week and thirty or thirty-one days of the month, in traditional observances, the five days ritual calendar is sacrosanct. Below is an explanatory diagram. These five days have their own names depending on the respective Esan towns. The first day as marked in the diagram is the most preferred day of burial. The second day which is Edeze or Edewor is considered traditional Sabbath and interments are to be done that day. Once interment has been done, Iganede or Ilede starts.

|

|

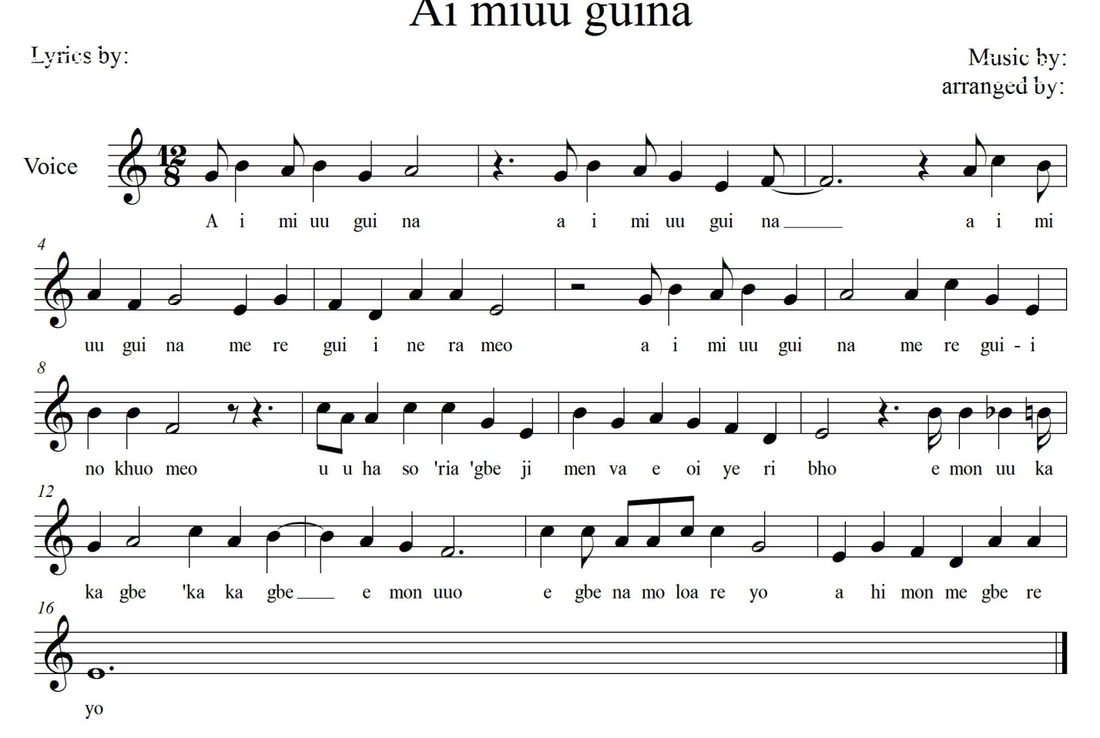

A i mi uu gui na

A i mi uu gui na A i mi uu gui na Me re gui ni ne meo A i mi uu gui na Me re gui no ‘khuo meo Uu ha so ‘ria ‘gbe Ji men vae oi ye ri bho E mon uu ka ka gbe, O ka ka gbe e mon uuo E gbe na monlon a re yo Ahi mon me gbe re yo |

[One cannot find death to pacify

One cannot find death to pacify One cannot find death to pacify I would have pacified for my mother One cannot find death to pacify I would have pacified for my wife When death comes here is no excuses matters relating to death are too critical too critical are its matter It is with one’s body that one goes No one borrows another body to go] |

This is an age old song which was also made popular by Christy Ogbah a notable Esan minstrel from Ugboha in Edo State of Nigeria in the early seventies. It is a dirge which captures the complexion of death. In the song, we get to be properly informed once again that: If it was possible to find death to pacify, I would have pacified it for my mother, If it was possible to find death to pacify, I would have pacified it for my wife, when death comes, there are no excuses, matters relating to death are too critical, too critical are its matter. It is with one’s body that one goes. No one borrows another body to go.

For the sake of space and the length of this paper, not all the songs will be transcribed. Some of them will simply be textual translation. The Okhuerie song below reads:

For the sake of space and the length of this paper, not all the songs will be transcribed. Some of them will simply be textual translation. The Okhuerie song below reads:

|

Okhue rie

Obha dan men Uwe miu’ kpo ‘dodo No’khue murio’ wa Okhue rie Obha dan men Uwe miu’ kpo ‘dodo No’khue murio’ wa |

[The parrot has flown away

I am not pained Did you see the beautiful cloth The parrot has gone with? The parrot has flown away I am not pained Did you see the beautiful cloth The parrot has gone with?] |

Without any in-depth appreciation, this song could be taken for an ode to the parrot. The song talks of the parrot flying away and carrying away its beautiful feathers. African parrots have grey colour around their bodies and very bright red coloured tail-this is referred here as beautiful cloth. This is why Aluede (2014) admonishes that such a song should be analysed using the principle of ambi-textuality. When in a burial context such a song is sung, it is obviously not an ode to the parrot but as a memorial to a dead personage who had a great deal of good attributes worthy of emulation.

|

Ole ghe ole rie o

O limen bhe gbe Abha ye miuu gui na O limen bhe gbe |

[He has said that he is going

This has given me goose pimples We cannot find death to appease This has given me goose pimples] |

The dead have said they are gone, it is really painful but death can never be appeased.

|

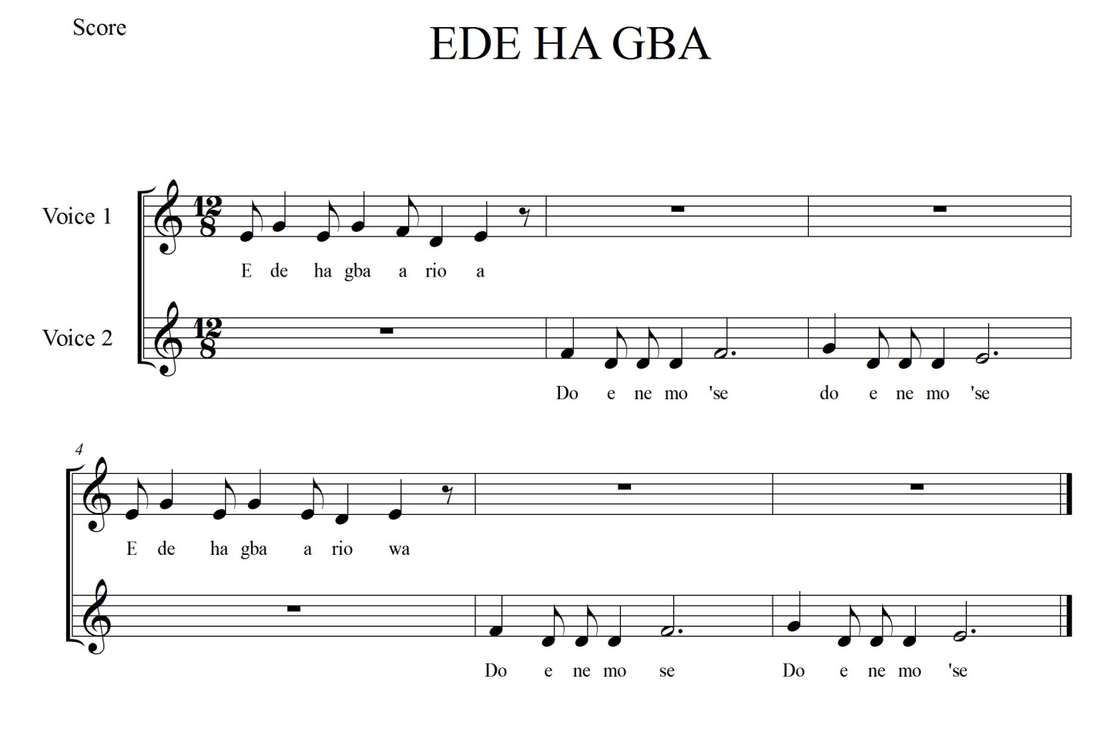

Ede ha gba a rio ‘wa

Do ene mo ose Do ene mo ose |

[At the apportioned time, one goes home

Welcome beautiful one Welcome beautiful one] |

The song means, at the appropriate time earmarked by God one dies, oh beautiful one. Whether beautiful, ugly, rich or poor, hear oh thou: Death is real and will always come at God's appointed time. This song is performed amidst interjections of words of advice which are often spoken verbally as interlude before the song is sung again and again or as interlude within the song verses. Sometimes they start by admonishing that “it may not be out of place to find twins who came into the world the same day not dying the same day. But remember that every mortal is configured uniquely and differently. With one hand a person may throw two stones simultaneously but they will never fall into the same place”.

In the same vein, Ruzvidzo (1997) says music fulfils a medicinal function when through total involvement, the dance reaches its climax and patients find cure. We need to first appreciate the fact that in most traditional African contexts, music and dance are concomitant. Therefore when dance reaches climax to engender healing, music is involved. In Esan traditional society, many variables aggregate to bring about the expected healing and some of them are: The rhythm of the music, the drumming and hand clapping, the soothing texts of the dirges, the collective involvement of all the members taking part in the performance and the spectators there present who have also passed through life’s trials and are there to share their experiences to aid quick recovery.

These observable influences of music on human beings have ab initio been highlighted by Mereni (1997, 2004) when he identified five different kinds of music therapy. To him, psycholytic music therapy is that kind of music provided for a client for the sake of spirit-freeing and liberating the mind from the grip of evil spirits, the anxiolytic type frees the client from the grip of anxiety. His observation is of much relevance to this paper is that while grieving, the griever becomes disturbed emotionally and then becomes unable to have good sleep as well as being unnecessarily anxious. Quite interesting and insightful is the fact that even in their primordial thinking, Esan people were able to identify the relationship between music and wellness. Thus in song bathing the bereaved for about three hours a day for five days in an uninterrupted sequence, the bereaved is freed from the firm grip of grief and are encouraged to boldly face the realities of life once again.

In the same vein, Ruzvidzo (1997) says music fulfils a medicinal function when through total involvement, the dance reaches its climax and patients find cure. We need to first appreciate the fact that in most traditional African contexts, music and dance are concomitant. Therefore when dance reaches climax to engender healing, music is involved. In Esan traditional society, many variables aggregate to bring about the expected healing and some of them are: The rhythm of the music, the drumming and hand clapping, the soothing texts of the dirges, the collective involvement of all the members taking part in the performance and the spectators there present who have also passed through life’s trials and are there to share their experiences to aid quick recovery.

These observable influences of music on human beings have ab initio been highlighted by Mereni (1997, 2004) when he identified five different kinds of music therapy. To him, psycholytic music therapy is that kind of music provided for a client for the sake of spirit-freeing and liberating the mind from the grip of evil spirits, the anxiolytic type frees the client from the grip of anxiety. His observation is of much relevance to this paper is that while grieving, the griever becomes disturbed emotionally and then becomes unable to have good sleep as well as being unnecessarily anxious. Quite interesting and insightful is the fact that even in their primordial thinking, Esan people were able to identify the relationship between music and wellness. Thus in song bathing the bereaved for about three hours a day for five days in an uninterrupted sequence, the bereaved is freed from the firm grip of grief and are encouraged to boldly face the realities of life once again.

Conclusion

In this seminal work, the author, first of all gave a historical and geographical background of the people whose musical culture was discussed. In an effort to properly discuss dirges and their nature, it was considered fit to examine the people’s opinion of death and kinds of death. Having laid this foundation, coping strategies in times of bereavement, the role of music, the texts of their dirges were subjected to some degree of scrutiny. While in the five days of uninterrupted music bathing we found fellow feeling and music to be soothing there by aiding recovery from the shock and pains associated with grief feeling, in the dirges, we found that their texts have ways of counseling and rehabilitating the grieving community members. It is the thinking of this Author that since music has this therapeutic potency, looking into the culture to extract, enhance and positively these indigenous practices for the betterment of humankind is advocated here. In doing these, no doubt, many more years of longevity will be added to our collective lifespan since life without music is unthinkable in the African parlance, it behooves on us to deploy it into good use.

References

|

This website is under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD