UDC: 784(669.1)

821.423.09:398

COBISS.SR-ID 109577481

_________________

Received: Nov 28, 2022

Reviewed: Dec 12, 2022

Accepted: Dec 25, 2022

Aesthetics and Utilitarian Essence

of Selected Yorùbá Folktales

Bamidele Omolaye

Department of Music, Faculty of Arts,

Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

[email protected]

Department of Music, Faculty of Arts,

Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

[email protected]

|

Citation: Bamidele Omolaye. 2023. "Aesthetics and Utilitarian Essence of Selected Yorùbá Folktales." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 8:3

|

Abstract

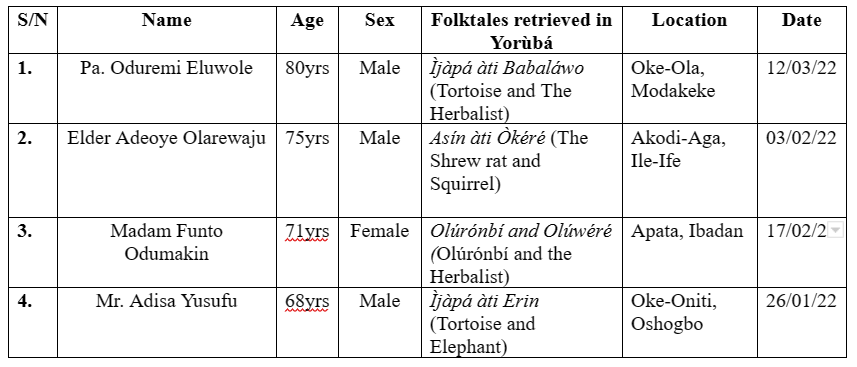

Folktales constitute one of the oldest traditional forms of education based on the method of delivery through oral tradition. Among the Yorùbá, folktale is a viable medium for transmission of cultural values, belief, history and philosophy of the community to the younger generation. The fact that African societies’ customs, morals and way of life are ingrained and codified in folktales shows the veracity of the indigenous knowledge system (IKS) embedded therein. This has contributed immensely to appreciating the culture, as well as the African people’s social norms. This study examines the aesthetics and utilitarian essence of African folktales, using four purposively selected Yorùbá folktales as case study. The goal of the paper is to bring the aesthetics and usefulness of African folktales, thus the songs are documented in a staff notation for musical analysis. Data for the study were collected through oral interviews and review of related literature. The selected Yorùbá folktales were examined through a descriptive method. Findings show that the essence of African folktales, as noticed in this present day, is being jettisoned and will soon become extinct by the current realities brought about by globalisation. This has greatly affected the cultural values which African folktales retain, maintain and disseminate. Hence, the need for the revitalization and digitization of African folktales to preserve the indigenous knowledge system deep-rooted in the narratives for future generations. This study concludes that the importance of African folktales would be better understood if properly harnessed, translated and notated from the musicological viewpoint, as it will further popularise the old tradition of storytelling in this modern age.

Keywords: folktales, cultural, utilitarian, indigenous knowledge, African folklore, yorùbá, songs |

Introduction

It will not be out of tune to state that folktales have been an age-long tradition where social norms of communities in Africa are passed down orally for generations. It is one of the oldest traditional forms of informal education, being one of the indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) for its method of delivery, mostly by elders, to further impact information and wisdom to the younger generation and from parents to their children. Kala (2012, 194) notes that some forms of traditional knowledge systems find expression in folktales, legends, folklores, rituals and songs, among others. Consequently, Okunade (2010, 33) pointed out that the indigenous knowledge system, which many people ignorantly describe as primitive, has been so long in existence in Africa and sufficed so much for the society's survival until the formal education introduction. In line with the above statement, Sibanda (2014, 1) asserts that while formal education is transmitted through institutions, culture is transmitted through music, dance, drama, folktales, folklores, legends, myths, proverbs, idioms, riddles and rhymes. The fact, notwithstanding, that the essence of African folktales, as noticed in this present day, is being jettisoned as a result of the current realities brought about by globalization, calls for urgent attention. To this end, Olorunsogo (2012) observes that:

<...> informal African traditional education has built into the practice of folktales, folklores, age-grade, rites and the celebration of festivals as a method of educating the young in the culture of its people; unfortunately, colonialism and its educational system which we imbibed had gradually and steadily attempted to erode traces of this traditional method of passing on the culture to the young. (Ibid., 257).

This statement clearly reveals how colonialism made us neglect areas which dignify our rich cultural heritage from across the world, most especially the knowledge derived from African folktales. This is why Ibekwe (2016, 84) asserts that it will be too bad or odd to allow global influences to have an impact on the primordial practice of knowledge transfer, which is a prerogative of any African child, most especially as exhibited in African folktales. It would not be an overstatement to mention here that every society across the world has an indigenous knowledge system by which they practice and draw essential tools for their existence. The essential attributes found in culture are used to enhance and impact moral values to the inhabitants of the society. The process and ability to recognize and utilize these essential attributes, which are identified as African folktales in the present study, is what Olisaeke and Aimiuwu (2016, 302) define as an “indigenous knowledge system”. In Africa, the indigenous knowledge system revolves around the children, who are given much affection and attention right from birth. In view of the above, Okunade (2010, 31) asserts:

<...> children learn about their immediate environment while watching through the activities that go on within their immediate society, as well as through folktales, folklores, folksongs among others. He/she appreciates the cultural values of the society as they grow and interact with people of the community. (p.31).

That music is an integral part of the African people cannot be overemphasised, as it is evident in all aspects of their culture. This is to say that across the socio-cultural spectrum of the African people, music plays a significant role in accompanying such activities in which African folktales belong. This study aptly describes African folktales as stories that originated and are entrenched in the socio-cultural ways of life of the African society, which are orally passed down to entertain, enlighten and educate people on moral values, as well as social norms of the African society. However, folktales songs are also known to function beyond entertainment. However, this is not peculiar to the Yorùbá people alone, but Africa in general. In view of this, Olatunji (2008) succinctly states:

<...> music among the Yorùbá people is beyond entertainment, as it is used to educate (especially the young ones about almost all the facets of culture and traditions). It is used to praise and to communicate (both in the physical and metaphysical realms). It is also used extensively in worship and as therapy for the drudgery of routines or to identify members of a particular occupation or association. (Ibid., 33).

Africans use this medium to instil uprightness and impact the younger generation. In fact, the interdependence of culture and education cannot be separated one from another. This is why Edward and Donaldson (2018, 2) affirm that a society devoid of any culture will have no definite educational organisation. As important as the combination of culture and education is to a society, folktale is believed to have the power to hold the community together. Through folktales, other societies learn about their history and cultural values, where such tales are rooted. In Hanlon (2000, 17), the above statement has been corroborated and expatiated. He notes that folktales are universal, and enhance globalisation of cultural knowledge. Hanlon’s assertion amplified the true essence, which folktales portray as an indispensable element and medium of transmission of indigenous knowledge system of the African people. Africans, like other people across the world, have an established norm that they consider valuable and necessary for the conservation and well-being of their children. There is no gainsaying the fact that every society possesses a distinct culture and way of life, which they skillfully narrate through various stories. It is in view of this that the Yorùbá people of Southwestern Nigeria, just like any other ethnic group across Africa, are known for their rich cultural heritage, which is embedded and exhibited through various modes such as folktales, folklores, folksongs, proverbs, myths, just to mention a few. Accordingly, David (2013) states:

<...> the indigenous culture of the Yorùbá has some certain phenomena that are embedded in it, as the case may be in other world cultures. This includes norms and tradition, belief system, folktales, folksongs, cultural philosophy, religion and literature. All of these constitute and form the way of life of the Yorùbá people. (Ibid., 100)

Over the years, folktales have played a significant role in the cultural matrix, especially within the purview of creative art, through which people get acquainted with the philosophy and cultural heritage of the indigenous African societies. However, it is believed that folktales, being an effective method of teaching, have more benefits because they involve many mediums of communication. Most importantly, songs accompanied by these stories help the children not only to follow the narratives, but to think deeply and reinforce their expectations about how to live a meaningful life. In addition, the retelling nature of the songs in-between the storylines, subsequently stanch to the hearts of both the narrator and the listeners, the message(s) which the story intends to pass across. Furthermore, the practical and fun nature of African folktales’ presentation through the use of indigenous language, animals as casts and plots, has also been known to engage and captivate the listeners’ minds.

It is important to note that African folktale narratives mostly revolve around one or two characters identified as protagonist and antagonist. These casts are portrayed with the use of personification of diverse animals such as lion, tiger, elephant, dog, snail, squirrel, tortoise, just to mention a few, as human characters in the stories to teach morals and traditions to the young in preparation of life's difficulties. From the pool of characters above, tortoise is mostly used in tales because of his distrustful and overzealous attitude (ológbón èwé). As a matter of fact, a tortoise that is known for his sneaky wisdom and insatiable attitude, oftentimes plays the role of antagonist by leading the protagonist to his or her demise. Furthermore, the tortoise is used as a protagonist because of his jovialness and kindness. This does not remove the fact that his demented greed, naivety, and pride remain his weakness. This will be evident in the stories discussed in the course of the study. However, this study is set not only to examine the aesthetics and utilitarian essence of African folktales by using the four purposively selected Yorùbá folktales, but the aim is to preserve the stories and the accompanied songs from extinction by documenting them in staff notation within the purview of musicological framework for posterity. To this end, studies on African culture have continued to receive wide coverage from eminent scholars of international repute across the world. Areas of African culture from its history, philosophy and tradition have been discussed from diverse fields of studies and humanistic viewpoints. Meanwhile, special attention might have been given to African folktales and its aphorism, historical reconstruction and folklores of various societies in Africa. Nonetheless, attention has not been given to the aesthetics and utilitarian essence of Yorùbá folktales. Engaging this area will help in revealing the usefulness of African folktales. More so, interested researchers would find the results of this endeavour useful and as a premise for further studies. This is the gap this present study intends to fill. Scope of the Study

There is no doubt that the essence of African folktales is being eroded as a result of globalisation. This has greatly affected the cultural values which African folktales retain, maintain and disseminate. This is why the paper, in the course of the study, solicits for the digitalisation of African folktales in order to preserve the indigenous knowledge system deep-rooted in the narratives for future generations. This study, however, is concerned with the aesthetics and utilitarian essence of African folktales; using the four purposively selected Yorùbá folktales. Hence, textual analysis of each of the selected Yorùbá folktales will be engaged, while each of the songs will be transcribed, notated and documented for posterity.

Theoretical Framework

Culture theory of Sardar (2004) as used by Serrat (2008) is employed in the study. Culture, according to Serrat (2008, 1), is described as the totality of a society’s distinctive ideas, beliefs, values, and knowledge. The fact remains that there is no society without its own distinct culture which binds its members. This is why culture is described as people’s way of life in a society. This is because it is the culture that gives them their identity as a people (Agbanusi 2015, 19).

Notwithstanding, it is possible that during a process of social collaboration, an individual who grows up in a certain environment is likely to be instilled with the culture of that society. While cultural activities, language, occupation, music and dance could be differentiated among communities across Africa, the purpose and utilitarian essence of some of their traditions in which folktales belong, remain intact. In discussing African cultural values, Idang (2015) explicates that: <...> it will be out of tune to presuppose that all African societies have the same explanation(s) for events, the same language, and same mode of dressing and so on. Rather, there are underlying similarities shared by many African societies which, when contrasted with other cultures, reveal a wide gap of difference. (Ibid., 97)

The statement above explains the fact that culture involves some traits which are peculiar to the inhabitants and as well, distinguishes them from other people or societies. The truth is that though cultural practices may be a distinctive identity in every society, there are some common values which run across these societies. As part of the culture and tradition of the African society, folktales, from time immemorial, have contributed immensely to learning, as they serve as channels for other communities to be acquainted with the social norms in African societies. Folktales, asides being a tool used in teaching moral values and impacting wisdom to the younger generation, also serves as a medium where cultural traditions are being propagated. The fact that people are the main object and ultimate purpose of endeavours to progress, a society’s culture is not just an instrument of communality, but it becomes an identity of the people where such culture is rooted.

Consequently, Offor (2014, 1) sees culture as the sum total of the attainments and activities of specific races or people, including their handicrafts, agriculture, economy, music, religious beliefs, traditions and language. It is interesting to note that culture theory is committed to an ethical evaluation of a society in order to understand its complex forms, expose and attempt to reconcile knowledge divides so as to overcome the split between tacit cultural knowledge and objective (so-called universal) forms of knowledge. This is corroborated by Nwamara (2020, 46) when he explains culture to be a complex whole which includes knowledge, morals, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by a man as a member of a society. Culture, however, is known to strengthen the way of life because it is powered by social beings through their distinctive ideas, beliefs and values. It becomes imperative, however, that the illustration technique ingrained in the transmission of African folktales makes it more effective for African children. Therefore, this theory is applicable to this study in the sense that the indigenous knowledge system derived from media such as folktale, folklore and folk songs is one of the oldest traditions of the African people which distinguishes them from other cultures. Therefore, this study is set to examine the aesthetics and utilitarian essence of African folktales, selected from the Yorùbá continuum. Definition of Operative Terms

Listeners, children, young, child and youths which were used interchangeably in this study, refer to the audience who are being impacted with the indigenous knowledge system deep-rooted in the African folktales.

Discussion of Findings

From the foregoing, this study, therefore, attempts to discuss the four randomly selected folktales. Thus, the narratives which will be presented and examined from the selected Yorùbá folktales will help in revealing the aesthetics and utilitarian perspectives of African folktales.

Ìjàpá àti Babaláwo [Tortoise and The Herbalist] In the olden days, the tortoise’s wife (yáníbo) was barren. The tortoise tried so hard to find a means through which his wife could conceive and have her own child. The tortoise began to look for help from different herbalists which he believed could solve his problem. After some time, he discovered one herbalist which was said to be powerful. He went to see the man and explained in detail what had happened. Thereafter, the herbalist consulted and appeased the oracle. After some time, the herbalist told the tortoise that his wife would conceive. He however, told the tortoise that he would prepare some concoctions to give to his wife to eat. The herbalist warned the tortoise not to make any attempt to taste from the concoction. The herbalist made the concoction and handed it over to the tortoise to take home for his wife to eat and after which, she would conceive. As the tortoise perceived the aroma of the concoction and noticed that it was pleasant, he tested the taste of the concoction, thinking that the small quantity he tasted would be of no effect to his body. However, the reverse was the case, as his stomach began to swell like that of a pregnant woman. He became very scared and went back to the herbalist. As he got there, he began to sing:

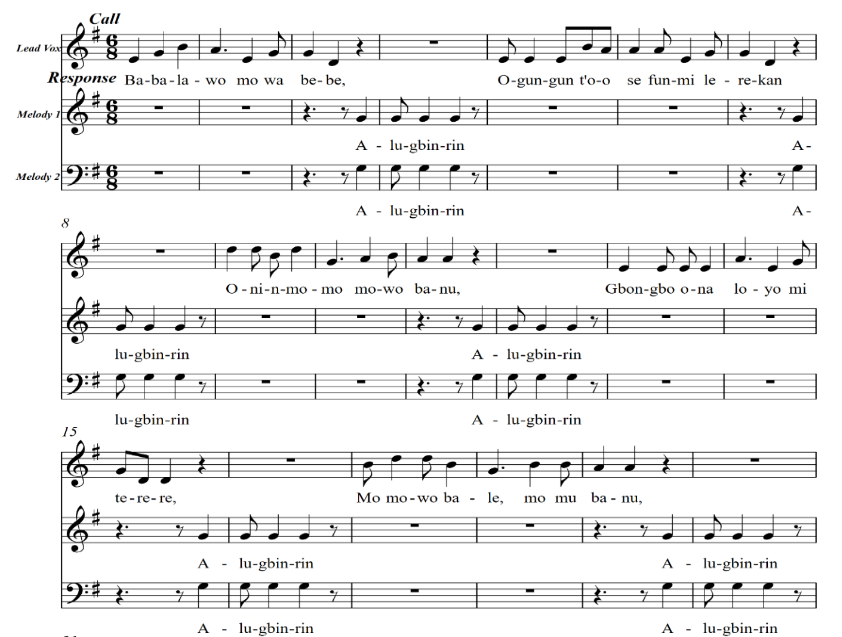

Call: Bàbáláwo mo wá bé bè

[Herbalist I came to beg] Response: Alugbinrin [Alugbinrin] Call: Ògùngùn tó se fún mi lérèkàn [The concoction you made for me earlier] Response: Alugbinrin [Alugbinrin] Call: Ó ní n mó mò mówó ba nu [He said I should not have a taste] Response: Alugbinrin [Alugbinrin] Call: Gbòngbò ònà ló yò mí tèrèrè [I accidentally hit a taproots and stumbled] Response: Alugbinrin [Alugbinrin] Call: Mo mó wó ba lè mó mú banu [My hand touched the ground and mistakenly touched my mouth in confusion] Response: Alugbinrin [Alugbinrin] Call: Mo bo júwokùn, ó rí gbendu [I look at my stomach as it began to swell] Response: Alugbinrin [Alugbinrin] Call: Bàbáláwo mo wá bé bè [Herbalist I came to beg] Response: Alugbinrin [Alugbinrin]

After listening to the tortoise’s plea through his song, the herbalist had compassion and forgave his attitude of theft and greediness by giving him another concoction and also healed his swollen stomach. The herbalist later gave him another concoction to take home for his wife to eat. As we know, attitude can never be hidden. Again, the tortoise tested the taste, and his stomach became swollen the second time. The tortoise was afraid again and went back to the herbalist, repeating the same song in the Example 1.

Although the herbalist was not pleased with him, he decided to help him the second time. The herbalist, again, had empathy and forgave his attitude of theft and greediness, healed his swollen stomach and gave him another concoction to give to his wife to eat, but greediness has taken over the tortoise and had become his lifestyle. For the third time, the tortoise tested the taste of the concoction, and his stomach became swollen. Shamelessly, the tortoise still went back to the herbalist. This time the herbalist refused to help him, because he had warned him twice. His stomach became swollen until it burst. That was how the tortoise killed himself because of his greediness. Anytime this narrative is told, children are expected to learn to be faithful and abstain from being self-centered. The narrative is also told for children to also learn from the repercussions in which the tortoise faced due to his greedy attitude and to be obedient to every instruction given by the elders. Asín àti Òkéré [The Shrew rat and Squirrel] Shrew rat (Asín) is a small rat with a long mouth and a distinctive smell. There is no place where the shrew rat (Asín) is present that one would not perceive its odour. Likewise, a squirrel is also a small rat with a hairy tail which usually jumps from one tree to the other. The squirrel loves palm-fruits. In the olden days, when animals sounded like men, a tortoise was selling dishes. One day, a tortoise took his dishes to the market for sale. As he was selling his dishes, he heard a rumour of a fight and immediately left his sales to watch the scene. As he got there, he saw a shrew rat (Asín) and squirrel exchanging combat. Then the tortoise decided to settle their quarrel, but was being sentimental in his judgement by siding with the squirrel and condemning the shrew rat (Asín). When the shrew rat (Asín) discovered that the tortoise was sentimental, he ignored the squirrel, faced the tortoise, and bit his nostrils. The tortoise shouted in agony and began to sing the song below:

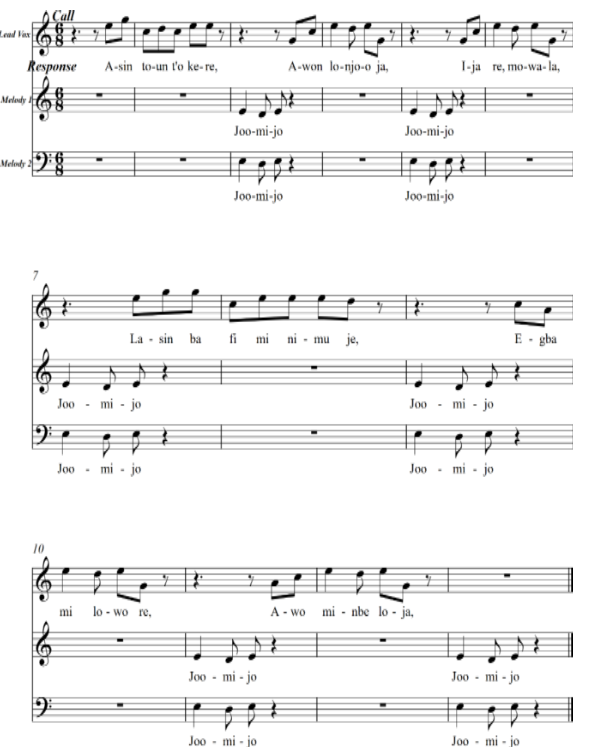

Call: Asín tòun t’ò kéré

[The Shrew rat and the Squirrel] Response: Jómijó [Jómijó] Call: Àwon ló jo n jà [The two were fighting] Response: Jómijó [Jómijó] Call: L’a sín bá fi mí nímú je [The Shrew bite my nose] Response: Jómijó [Jómijó] Call: Ègbà mí ló wó rè [Save me from his hands] Response: Jómijó [Jómijó] Call: Àwò mi n be ló jà [My dishes were in the market] Response: Jómijó [Jómijó]

As the tortoise was singing in agony, the other traders and passers-by came to his rescue, but unfortunately, the shrew rat (Asín) had already damaged the tortoise's noise with his prolonged bite before he was rescued. This was why the tortoise's nose was short and disfigured till date. This narrative is told in order to redirect children’s mind-set from being sentimental and to always mind their business. Most importantly, children are also expected to stay away from fights and quarrels.

Olúrónbí àti Olúwéré [Olúrónbí and the Herbalist] In the olden days, there was a certain woman whose name was Olúrónbí. This woman was barren, she could neither conceive nor have a child. For a long time, she looked for a child but all to no avail. Instead of waiting for God’s time, she went to Olúwéré, an herbalist. She did this because her contemporaries had already given birth and had their own children. One day, she rose up and went to Olúwéré (herbalist). With desperation, she vowed to return the child to Olúwéré once she had one. This vow was exceptional because there were goats and sheep that women in her situation used to pay back as a vow to Olúwéré (herbalist). Meanwhile, Olúrónbí conceived and gave birth to a girl whom she named Apónbíepo. As Apónbíepo was growing, Olúrónbí forgot her vow which she made with Olúwéré (herbalist). When Olúwéré (herbalist) expected Olúrónbí to come back to pay her vow and did not see her, he decided to pay her a visit. As soon as she got to Olúrónbí and saw her child, Apónbíepo, Olúwéré (herbalist) grabbed the child and took her away. This child , Apónbíepo, started crying while Olúrónbí ran after them. Eventually, Olúwéré (herbalist) disappeared into a tree with the child, Apónbíepo. Olúrónbí started persuading Olúwéré (herbalist) with tears on her face to return her child, Apónbíepo. Instead of Olúwéré (herbalist) to return the child Apónbíepo, he responded with the song below:

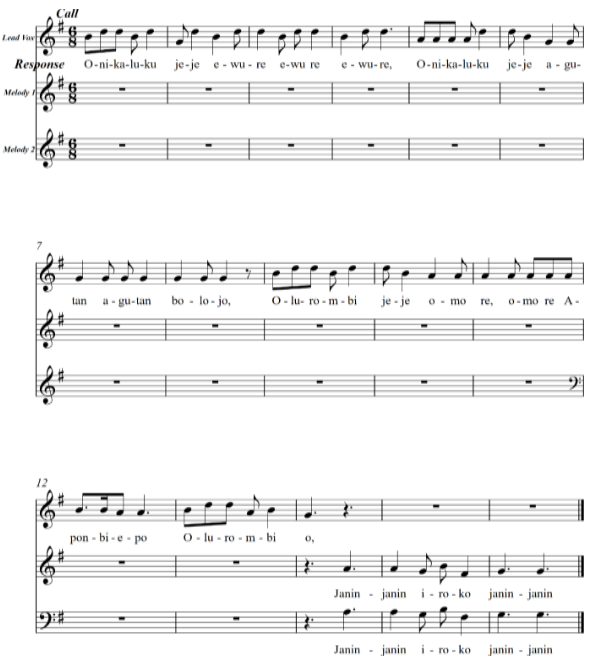

Solo: Oníkálukú n jèjé ewúré, ewúré, ewúré,

[Each person vows a goat! goat! goat!] Oníkálukú n jèjé àgùntàn, àgùntàn bòlòjò [Each person vows sheep, a well-fed sheep,] Olúrónbí n jèjé omo rè, omo rè Apónbíepo [Olúrónbí vows her child, her child Apónbíepo] Olúrónbí oo [Olúrónbí oo] Chorus: Janin – janin, Ìrókò janin-janin [Mighty-mighty Ìrókò tree, mighty mighty] Solo: Olúrónbí oo [Olúrónbí oo] Chorus: Janin – janin, Ìrókò janin-janin [Mighty-mighty Ìrókò mighty mighty]

This was how Olúrónbí lost her child (Apónbíepo). Anytime this narrative is told, children are expected to learn that it is not good to make a pledge beyond their ability and should not be in haste to make a vow. So also, it is always important to cast all our cares on God and not to be too desperate to seek for answers because God does not forget anybody.

Ìjàpá àti Erin [Tortoise and Elephant] In the old days, there was a certain village. The King of the village died, and the community wanted to install another. According to the village custom, they had to consult the oracle before they could nominate another person. Meanwhile, whoever the oracle selected would be automatically crowned the King. While the villagers performed the rites required, the oracle informed them to make a sacrifice, using an elephant as the object of the sacrifice before they could install another King. There is no doubt that elephants are huge animals that cannot be easily captured. In fact, there is a saying that a King that would capture an elephant does not exist. So also, you can never tie an elephant to a tree using a rope, as the elephant will uproot the tree. The community, however, began to deliberate on how they could get an elephant for the sacrifice. With all the attributes bestowed on the elephant, it became a burden for the community, not knowing how they would capture such a huge animal for sacrifice. This request from the oracle caused a commotion even between the elders among the villagers, as it saddened their hearts. As we are all aware of the saying that where there is ‘I will kill you’, there is also ‘I will save you’. That is, where there is a No, there is also a Yes. The villagers were in this situation when the tortoise came, and assured them that he would bring an elephant into the village alive. Having heard how the tortoise boasted that he would bring an elephant into the village unharmed and unhindered, the villagers let him do what he could. It is generally believed or assumed that a tortoise is a wise and canny animal. This is why he baked some cakes with lots of honey and went straight into the thick forest. When the tortoise got there, he saw an elephant and began to hail as to how the elephant was the head of all other animals, and that there was no animal who could act contrary to his instructions. When the tortoise saw that the elephant was so happy about how he hailed him, he told him the reason he came into the thick forest in search of him. The tortoise told the elephant that the villagers wanted him as their King, and the elephant laughed at him to scorn. The elephant told the tortoise that human-being was harsh and wicked. After the elephant had said this, the tortoise served the elephant with the cake he had baked with honey. As the elephant was eating the cake, and since it tasted so sweet, he changed his mind and decided to follow the tortoise. The tortoise told the elephant that when he became the King, he would be coming to visit him. The tortoise then asked the elephant if he could climb and ride on his back, so that the villagers could see how intimate they were, and additionally their journey would be faster. Quickly, the elephant carried the tortoise and headed to the village. As they were going, the tortoise started singing the song below:

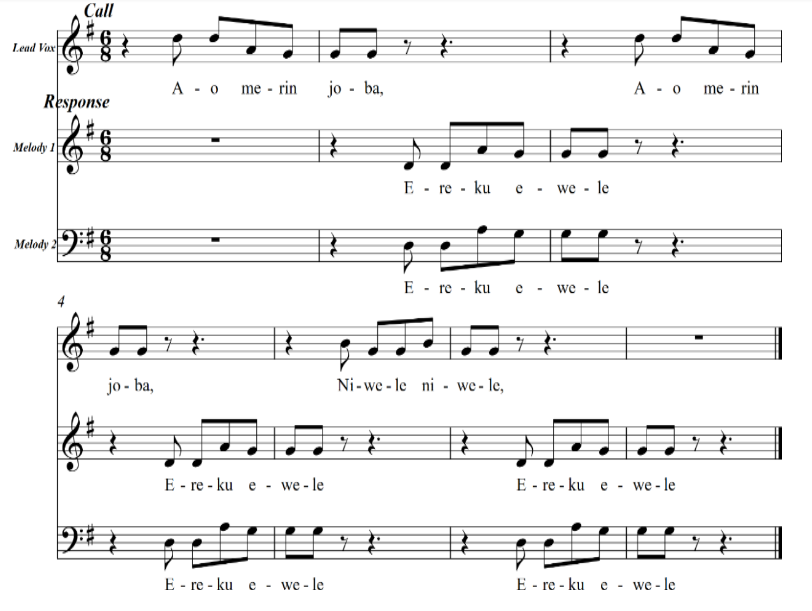

Call: A ó mérin J’oba

[We shall install the elephant] Response: Èrèkú e we le [Easily, easily] Call: A ó mérin J’oba [We shall install the elephant] Response: Èrèkú e we le [Easily, easily] Call: Ní we le, ní we le, [With ease, with ease] Response: Èrèkú e we le [Easily, easily.]

After they had journeyed for some time, the elephant wanted to change his mind and turn back. The tortoise swiftly fed the elephant with another cake. The elephant was so happy, while they continued with the journey. Meanwhile, before they entered the village, the tortoise had already instructed the villagers to dig a very deep pit and cover it with fine and expensive clothing materials. He also instructed the villagers to place an expensive chair and make a throne on the pit they had dug. As the tortoise and elephant got into the village, the tortoise raised the same song (see Example 4). The villagers were so happy and filled with joy and started to sing along with the tortoise. As they got to the village, the tortoise asked the elephant to sit on his throne without the elephant knowing it was a pit. Eventually, the elephant sat and sank into the pit, while the hunters shut at him sporadically till he died. This was how the tortoise deceitfully brought the elephant into the village.

This narrative is told to enlighten the children on the fact that when they determine and focus their attention on a particular goal, they will definitely achieve it. The story is also used to discourage children from being greedy, deceitful and to be content with what they have. The tale also teaches the children to not condemn or underrate anybody. When one looks at the fragile nature of the tortoise, one would have concluded that a tortoise can never bring such a huge animal into the community for sacrifice. The fourth folktale narrated in this study makes it clear that it is not a good idea to underrate anybody, as well as overrate oneself above others. Part of the message which the folktale passes across is that there is no problem without a solution. In the story, it was vivid that the tortoise availed himself and solved the problem of the community by bringing the elephant for the sacrifice. Analysis of the Accompanied Songs of the Selected Yorùbá Folktales

Music is one of the artistic forms through which culture is expressed. It is important to state that songs emanated from African folktales belong to the traditional, folk music category. In view of this, Omolaye (2014, 5) opines that traditional songs maintain and safeguard the cultural tradition and history of the people, entrenched in the music and passed from one generation to the other. Therefore, these songs are usually in two musical forms: Solo and Chorus, and Call and Response pattern from the pool of musical forms in which African music is performed. The solo and chorused form possesses antiphonal character, where the lead singer raises the song and the chorus responds. This is exemplified in the excerpt three of the selected folktales. The call and response pattern is a situation where the lead singer calls while a group of people responds with another text, as evident in excerpt one, two and four of the selected folktales.

Consequently, the songs employed an hemitonic pentatonic pattern, being a scale without half step. This is because the auditory properties of the Yorùbá language pave the way for the ordering of sounds on a frequency related scale. It is important to mention that traditional folk music has no fixed pitch since they are passed orally. Hence, the lead singer determines the pitch of the songs during performance, while the tuning also depends on his/her vocal quality. In addition, the time signature of the four selected folktales employed compound duple metre (68). Furthermore, the text-settings of the songs are in syllabic structure, i. e. a syllable to a note, used to protect the tonal inflection of the indigenous language, which is the medium of transfer. The songs’ textual structure as observed in the two musical forms is in binary structure. All these musical elements and nitty-gritty are parts of the musical aesthetics, used to make the songs well-structured, melodious and easily committed to memory. Aesthetics of African Folktales

According to Idang (2015, 105), the concept of aesthetics in Africa is grounded on the fundamental traditional belief system, which gave vent to the production of the art. Meanwhile, Abiodun (2001) in Sanga (2017) explains the three main concepts important in understanding Yorùbá art, its relationship with language, culture and aesthetic sensibility, to include àsà – culture, ìse – tradition, and ìwà – character (Ibid., 317). Folktale is one of such arts where culture and traditions of the people, as well as attitudes and patterns of behaviour, are decoded through a very simplistic expression by the characters in the tales. Therefore, the beauty of these folktales’ songs during the presentation is that the listeners are given a sense of participation, as African music is known to be participatory. This is evident in not just the four selected folktales examined in this study, but all, as they draw the attention of the listeners. The African concept of music aesthetics, therefore, is beyond the quality, beauty or enjoyment of music, as it includes the functionalism of such music (Forchu 2012, p208). Therefore, it is the functionality of such art, as exemplified in songs which accompany folktales, that enhances the aesthetics of other activities that go with it. As a matter of fact, these songs bring to bear the sense of aesthetic value among African people.

It is expedient to note that the aesthetic development of African folktales began from the real setting, known as one of the moonlight genres from time immemorial, being the space where folktales are performed. In Africa, folktales are usually performed at night, especially during harmattan season, while children gather to listen after their daily works. Africans are generally industrious, so they cannot afford to be affected by any other activities. This is because every activity performed in African society is organised in accordance with the tradition. According to Africans, there is time to work and time for leisure. The context at which folktales are performed is mainly in the night. This further explains the aesthetic space where folktales are performed, specifically, during the moonlight in an open arena. In addition, the aesthetic values of African folktales are also entrenched in words, which has no logical translation in the narratives. An example of such a word is Álúgbínrín. Therefore, folktales are performed in that kind of environment after people have finished their daily works in a kind of relaxation atmosphere. There is no doubt that farming is a major occupation in Africa. This makes the rainy season period the time for cultivation, planting and other activities therein. The Utilitarian Essence of African Folktales

Folktales have a unique narrative construction and description used to inculcate effective moral values to the young, without naming or defaming anyone. This is also exemplified in Yorùbá folktales, while its contents do not differ from tales from other parts of the Africa continent. The utilitarian perspectives of African folktales are enormous. This is why Manda (2015, 600) refers to it as euphemistic and witty ways of criticising and accepting human fallibility of praising success and warning against bad human practices and behaviour, and as forms of entertainment. They are also used to discourage children from being self-centred and disobedient. This is affirmed by Mphande (2014, 54) when he notes that the contents of the Malawian folktales mostly relate to human society and centre around, inter alia, greed, jealousy, foolishness, inheritance and succession, witchcraft, and the importance of umunthu or one’s identification with and submission to collective social thinking that defines most Bantu societies. In the same vein, Uwah (2008, 87) notes that the above themes are common themes which Nollywood films feature, as they are quite popular among African rural audiences. Meanwhile, songs which accompany the tales, apart from helping the listeners to develop retentive memory, are used to instil wisdom in their hearts. Based on this, the study observes different essences by which African folktales could be used to appeal to the model of “thinking locally and acting globally”, especially among the young generation. These various ways include, but are not limited to:

Entertainment: African folktales create an avenue for children to socialise and relate with other children. The essence of the songs, which are set in-between African folktales, also helps the children to retain the message(s) embedded therein, and thereby develop retentive memory, follow a plotline or recall a sequence of events. The performance of the songs gives the children the capacity to relay stories to their peers, as well as the learning outcomes.

Teaching: African folktales are used to teach and pass down ethics and right behaviour to the next generation. It can never be an overstatement to say that African folktales help children develop strong reading skills, study other peoples’ cultures and model positive character traits. Consequently, they also make it easier for children to differentiate between good and bad characters. In addition, they teach the children how to make effective decisions. Chapman (1978, 117) in his view, sees education as a means of cultural heritage and the extension of social consciousness. Research has shown that children learn faster and assimilate easily in school, because of the use of music and storytelling methods in teaching at the pre-, primary and secondary schools. Cultural Awareness: They help children to know about taboos in the culture and tradition of the Yorùbá. It reminds children of the traditional occupations in the past, core values and norms of the Yorùbá culture. They also help children to learn about the history and philosophy of the Yorùbá people. African folktales carry lots of information which help the society in maintaining order and unity. Moral Values: They help children to think deep and reinforce their expectations on how to live a meaningful life. It helps children to learn how to dress and behave. There is an adage that says: Bí omodé bá ni ìtàn, àgbà ló lò we – meaning, “If folktales belong to the children, adults are known with proverbs.” That is, while the folktales are so useful among children, adults are believed to be the carrier and major patronage of proverbs. Through folktales, children learn language, culture, tradition, custom and norms. Folktales are not just for fun. They are used to achieve a desire for sustainability in the community. That is, through folktales, concerted effort as a result of the people’s communality and unity can be harnessed in order to arrive at sustainable development within the community. Folktales are used in a way to promote patriotism among the children, so as to be patriotic to their society, nation, and continent at large. African folktales promote social values and open a space for the understanding of the social norms, concepts and thoughts of the society in order to draw positive change among its inhabitants. African folktales make us understand the environment we live in and how to depend on one another. Although folktales are known to be transmitted orally, there is a need to further revitalise and digitise African folktales in order to acquaint children of today with the cultural and moral values embedded in African folktales. The Need for Digitalisation of African Folktales

Almost all human endeavours in today’s context are being digitised to meet the trends in global community space. Hence, the need for digitalization of African folktales. Some of these folktales could either be revamped or be told as they were. As Usman (2013, 40) rightly notes that folktales can be retold in any fanciful way, as nobody has copyright over them. This compels the call for the digitization of African folktales for global consumption. It is pertinent to state, however, that the dissemination of African folktales has always been an oral tradition from generation to generation. The effectiveness of this medium, as noticed today, cannot be compared to the media. This is because the African folktales’ tradition is gradually in decline. This has greatly affected the cultural values which African folktales disseminate, hence, the best time for the digitalization of African folktales. The rapid way in which technological advancement is springing up and changing the society into a global community further confirms the need for the digitization of African folktales. This is evident in the Western world, as they have been employing this medium, by creating and redirecting their fairy tales into films for children. As a result, many African children are not familiar with African folktales, as they are used to watching the foreign cartoons. Watching those cartoon films while growing up has a negative impact on their behaviour, because lessons from those cartoons are derived from foreign cultures. Therefore, African scholars need to put in more effort in order to revitalise the essence of African folktales in this modern era.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study has explained African folktales to be a unique narrative construction and description which is used to inculcate effective moral value to the young without naming and defaming anyone. This study has also revealed the utilitarian essence of African folktales and the indigenous knowledge system embedded therein. The aesthetic progression of African folktales is said to have begun from a setting known as moonlight from time immemorial, being the space where folktales are performed, especially during harmattan season, while children gather to listen after their daily works. Although African folktales are known to be transmitted orally, the fact remains that all aspects of human endeavours today are being digitised. It is however expedient to revitalise and digitise African folktales in order to acquaint children of today with the cultural and moral values embedded in African folktales. Effort from African scholars at this present time is extremely required so as to revitalise the essence of African folktales in this modern era. In conclusion, it is expected that the importance of African folktales would be better understood if properly harnessed, as it will further popularise the old tradition of storytelling in this modern age.

This study, therefore, recommends that African folktales, being one of the mediums where indigenous wisdom and moral values are passed and transmitted be revitalised and digitalised, so that the practice will continue to impact positively to the younger generation. In addition, once adequate attention is given to this African cultural practice, it is certain that the residue of knowledge passed on to children through African folktales would be preserved from possible extinction. |

References

|

This website is under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD