UDC: 78.071.1(=163.41)(4)"19":929

378.18(=163.41)(4)"19"

COBISS.SR-ID 33218057

_________________

Received: Sep 05, 2020

Reviewed: Nov 08, 2020

Accepted: Jan 13, 2021

#6

FOREIGN STUDIES OF THE SERBIAN COMPOSERS

CRUCIAL IN FORMING NATIONAL MUSIC CULTURE

Nadežda Mosusova

Musicological institute SANU (Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts), Belgrade (Serbia)

[email protected]

Musicological institute SANU (Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts), Belgrade (Serbia)

[email protected]

|

Introduction

The purpose of the paper is to add the new facts to the history of musical studies in quoted countries, i. e. at Moscow, Prague, “The European Conservatory”, and Vienna Conservatory before and after the Great War. Actual research can probably also contribute to the history of nowadays neglected or forgotten appearance of Slavonic musical reciprocity, maintained in the XIX century and strongly improved in the European interwar period between two then newly formed states: Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia.

Accordingly, it is important to think about the Serbian composers born in the 19th century, because of their shaping of musical life in their country after models they inherited from the big European centers. In this sense it is important to get to know more details about Serbian musical students abroad, to research what they exactly wanted, what they expected from their investments in musical studies, and what their results were. Probably, in some moments they did not expect much, but the love of music was stronger than the uncertain existential future. Of course, they had plans and dreams to improve musical status in their country, and to establish a national style in their compositions. In Serbian music at that time that was like creating instrumental works which would be properly performed.

|

|

Another heir of Stevan Mokranjac, succeeding Miloje Milojević as a conductor in the Belgrade Choral Society, Kosta Manojlović (1891-1949) was the only one who left a testimony about his studies as a private diary (unpublished), received also the Serbian Orthodox Church’s scholarship, soon after Hristić.

|

Manojlović went to Moscow in March 1912 trying to enter the Conservatory. After Manojlović’s memoirs, Jovan Zorko (1881-1942 ), a Belgrade Music school violin teacher, former Moscow student, recommended him to Nikolai Sokolovsky (1865-1921). The latter, a professor of violin and theoretical disciplines at the Moscow Conservatory found Manojlović unprepared for the Conservatory. In addition, Moscow Conservatory was at the time under the leadership of Mihail Ipolitov-Ivanov (1859-1935).

Sokolovsky recommended Manojlović to consult Alexander Ilynsky (1889-1920). Namely, after Marina Rachmanova, then participant of the conference, the students (also of Russian provenience) who could not enroll at the Moscow Conservatory as found unprepared were sent to the Moscow Philharmonic Society of Music and Drama whose director Ilynsky, known for his ballet “Noure and Anitra”, was a former composition student of Woldemar Bargiel and piano pupil of Theodor Kullak in Berlin at the Neue Akademie der Tonkunst.

After being informed that the preparation for the Moscow Conservatory can last too long (maybe two years), the Serbian candidate decided to change the place of music studies and went after a short stay in Russia to Munich. There Manojlović took private lessons by professor Richard Meyer-Gschrei, and successfully passed examinations for Munich Conservatory. It is to be noted here that nobody found the coming students at the Prague Conservatory unprepared. Let us remember some of them, such as Petar Konjović, who appeared in front of Karel Stecker (1861-1918), the rector of the Prague Conservatory, in 1904 with the one full-length opera, and was enrolled immediately in the second year, as well as Božidar Joksimović who graduated from the same Conservatory in 1896.

It is very interesting to notice what Kosta Manojlović, the “unprepared” one, had done during his two months Moscow sojourn (at the time of Orthodox Easter), living between Serbia and Russia. From Manojlović’s memoirs we learn about his frequent visits to churches, concerts and theaters, Bolshoy and Zimin, his listening to the Russian operas mainly by Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov. But when this Serbian student saw and heard Wagner’s Lohengrin, all previous Moscow’s musical experience was forgotten, except the Russian church holy services in cathedrals and concerts, and the magnificent Moscow Synodal Choir with 500 singers (Manojlović 1946, 35-37).

Concerning operas, in the case of Manojlović, he had to visit Russia (which is a dream of many musical Serbs) to discover Richard Wagner instead of Modest Mussorgsky. In this spectrum, we have to mention affinity for Wagner shown by Milenko Paunović (1889-1924) who after Prague studies made his diploma in Leipzig where he studied under Max Reger, Stefan Krehl and Hugo Rieman, writing music dramas of his own style.

Ties with Bulgaria

During the Great War and afterwards, Kosta Manojlović was accomplishing his musical knowledge in England from 1917 till 1919. He neither became a music dramas nor Russian music propagator. His Slavonic feelings were shed on the nearby Sofia.

After the WWI Manojlović was occupied with restoring musical ties of Bulgaria with SCS Kingdom. The action was met with much opposition from Serbian society still sensitive to the war experiences, when Serbia and Bulgaria were enemies. The musical friendship between two kingdoms, Yugoslav and Bulgarian could be restored in the late thirties when Serbian composers visited Sofia and Pancho Vladigerov (1899-1978) paid a visit to Belgrade. This was an opportunity for many concerts devoted to Serbian and Bulgarian music.

After the WWI Manojlović was occupied with restoring musical ties of Bulgaria with SCS Kingdom. The action was met with much opposition from Serbian society still sensitive to the war experiences, when Serbia and Bulgaria were enemies. The musical friendship between two kingdoms, Yugoslav and Bulgarian could be restored in the late thirties when Serbian composers visited Sofia and Pancho Vladigerov (1899-1978) paid a visit to Belgrade. This was an opportunity for many concerts devoted to Serbian and Bulgarian music.

New states in Europe and Milojević’s Doctorate

Miloje Milojević, after studies in Munich and war years spent in France, has turned his interests toward Czech music. The Slavonic solidarity was in full run between two newly made states, Czecho-slovakia and SCS Kingdom with many scholarships delivered for Yugoslav students, including musicians. Although enchanted by Richard Strauss (Salome in Munich) and Claude Debussy (in Paris), Milojević gave priority now to Bedřich Smetana, first by publishing his biography in Belgrade in 1924.

Choosing Charles University in Prague for his dissertation concerning Smetana’s harmonic style (Konjović 1954, 186-190), Milojević accomplished his thesis under the leadership of the musicology professor (from 1908/9) Zdenĕk Nejedlý (1878-1962) in 1925. Cметанин хармонски стил [Harmonic Style of Smetana] was published in Belgrade 1926. In 1984 at the musicological conference held in Negotin (as part of the Festival Mokranjčevi dani [Days of Mokranjac]), devoted to work of Miloje Milojević, our colleague from Brno Jiří Vysloužil delivered a paper about Milojević’s dissertation. (The text has not yet been published.)

It is worth mentioning that no evidence has been found about the “Mediterranean” studies of Ljubomir Bošnjaković (1891-1987) who graduated from Naples conservatory. Jovan Srbulj (1893-1966) studied in Vienna and Italy after the war. Jovan Bandur (1899-1956) also started at Vienna but graduated at Prague Conservatory, being one of the collaborators of Miloje Milojević’s actions in Yugoslav-Czechoslovakian relationship.

Passing the Great War number of Prague musical Serbian students increased: Aleksa Ivanović (1888-1940), Milivoje Crvčanin (1892-1978), now from Yugoslavia (Kingdom of Serbs, Croates and Slovenes), the latter making his composition diploma in 1922 with Bohuslav Foerster at the now State Music Conservatory.

Crvčanin was the second Serbian musician who defended his thesis at the Charles University, by Zdenĕk Nejedlý in 1929 and the only Serb who was lecturing at the Prague Conservatory, namely teaching the theory of Othodox church music 1932-1941. In the Serbian music studies this fact is not sufficiently emphasized, mentioning after Miloje Milojević only Vojislav Vučković and Oskar Danon as musicological doctorands at Prague University.

Crvčanin was at that time also a member of the Yugoslav diplomatic service in Prague. As a diplomat, Milivoje Crvčanin was also curator of the Serbian Orthodox part of Olšany Cemetery of the Great War in Czechoslovakia, which Yugoslav ambassador Djoko Stojičić in Czech Republic 1994-2001 brought to full restoration supported by Czech government.

Furthermore, with Czech capital was tied up as a representative of Yugoslav diplomacy Petar Bingulac (1897- 1990), lawyer and composer, a French music pupil who, while obtaining his knowledge at Schola Cantorum under Vincent d’Indy, was studying law in Paris during 1920s. (Milikić 2020)

Another two Serbs, also from Croatia-Austro-Hungary, Marko Tajčević (1900-1984) and Mihailo Vukdragović (1900-1986), the Prague students, were important in improving the music status of their land. They are chronologically closing the Serbian composers’ of foreign studies circle born in the XIX century. Majority of them were remembered as excellent pedagogues in theoretical disciplines and free composition.

Several excelled as leaders of mainstream musical institutions in SCS Kingdom, and composers of high rank, in later Yugoslavia. Another part of foreign students remained modest but unavoidable masters of their local places.

Choosing Charles University in Prague for his dissertation concerning Smetana’s harmonic style (Konjović 1954, 186-190), Milojević accomplished his thesis under the leadership of the musicology professor (from 1908/9) Zdenĕk Nejedlý (1878-1962) in 1925. Cметанин хармонски стил [Harmonic Style of Smetana] was published in Belgrade 1926. In 1984 at the musicological conference held in Negotin (as part of the Festival Mokranjčevi dani [Days of Mokranjac]), devoted to work of Miloje Milojević, our colleague from Brno Jiří Vysloužil delivered a paper about Milojević’s dissertation. (The text has not yet been published.)

It is worth mentioning that no evidence has been found about the “Mediterranean” studies of Ljubomir Bošnjaković (1891-1987) who graduated from Naples conservatory. Jovan Srbulj (1893-1966) studied in Vienna and Italy after the war. Jovan Bandur (1899-1956) also started at Vienna but graduated at Prague Conservatory, being one of the collaborators of Miloje Milojević’s actions in Yugoslav-Czechoslovakian relationship.

Passing the Great War number of Prague musical Serbian students increased: Aleksa Ivanović (1888-1940), Milivoje Crvčanin (1892-1978), now from Yugoslavia (Kingdom of Serbs, Croates and Slovenes), the latter making his composition diploma in 1922 with Bohuslav Foerster at the now State Music Conservatory.

Crvčanin was the second Serbian musician who defended his thesis at the Charles University, by Zdenĕk Nejedlý in 1929 and the only Serb who was lecturing at the Prague Conservatory, namely teaching the theory of Othodox church music 1932-1941. In the Serbian music studies this fact is not sufficiently emphasized, mentioning after Miloje Milojević only Vojislav Vučković and Oskar Danon as musicological doctorands at Prague University.

Crvčanin was at that time also a member of the Yugoslav diplomatic service in Prague. As a diplomat, Milivoje Crvčanin was also curator of the Serbian Orthodox part of Olšany Cemetery of the Great War in Czechoslovakia, which Yugoslav ambassador Djoko Stojičić in Czech Republic 1994-2001 brought to full restoration supported by Czech government.

Furthermore, with Czech capital was tied up as a representative of Yugoslav diplomacy Petar Bingulac (1897- 1990), lawyer and composer, a French music pupil who, while obtaining his knowledge at Schola Cantorum under Vincent d’Indy, was studying law in Paris during 1920s. (Milikić 2020)

Another two Serbs, also from Croatia-Austro-Hungary, Marko Tajčević (1900-1984) and Mihailo Vukdragović (1900-1986), the Prague students, were important in improving the music status of their land. They are chronologically closing the Serbian composers’ of foreign studies circle born in the XIX century. Majority of them were remembered as excellent pedagogues in theoretical disciplines and free composition.

Several excelled as leaders of mainstream musical institutions in SCS Kingdom, and composers of high rank, in later Yugoslavia. Another part of foreign students remained modest but unavoidable masters of their local places.

Results of realised and non realised Slavic collaboration

Mentioning again strong slavophile tendencies practiced among Viennese Orthodox population during the life of Kornelije Stanković which was very much mingled with the Russian influence, we are underlining the new trends of Slavonic mutuality at the end of XIX among South Slavs and Russia. Stevan Mokranjac became already the icon of Serbian music, touring as conductor and composer, with Belgrade Choral Society mainly Slav lands reaching Russian main towns. Mighty Five, not yet Mussorgsky, became already known in the Kingdom of Serbia, thanks to Mokranjac. But in the chain of musical events of mutual recognition there was a personality missing in the whole story of revealing of Russian opera music: Mihail Glinka.

From Moscow to Belgrade, in the 1880s, the score of Glinka’s Life for the Tzar was sent from the composer’s sister Lyudmila Shestakova. According to Rahmanova, this was due to the initiative of strongly pan-slavic oriented Milij Balakirev (1837-1910). This was also a diplomatic gesture from Russia. The score was sent through Serbian embassy in Sankt Petersburg, delivered to the Serbian government. Stojan Novaković preceded the score to the National Theater of Belgrade. The fact was noted by state archives, but nobody knows what happened with Glinka’s score. Never mentioned afterwards and never performed. In fact, Glinka’s Life for the Tzar was performed in the Belgrade House of Russian Culture in 1933, but not after that score.

Supposedly Glinka’s opera was lost in the damaged National theatre during the Great War which was a great loss. If it had not been lost it could have been performed before 1914, when the modest Belgrade opera started with Verdi and Puccini. (My laments about the lost opportunity are joining the colleague’s statement that “the paths of Serbian music after Life for the Tsar [performed] in the right time, could be different!” (Pavlović 1994, 157)

As stated, Glinka was not unknown in XIX century Serbia, due again to Stevan Mokranjac who as a member of, for this occasion broadened Serbian string quartet, played violin in 1889 in the Piano Sextet of Russian Master. Afterwards, regarding presumably the shortage of suitable opera soloists, choral parts of the Glinka’s opera were sung by Belgrade Choral Society under Mokranjac, but the complete opera performed would be a natural link in the investigation of the continuity of Russian music. The link between, let us say, Bortnyansky and the Mighty Five. An important pattern for Stevan Mokranjac, as it was, it could also be a model for Petar Konjović, who before his regular studies in Prague learnt instrumentation from Carl Maria von Weber’s Freischütz. Why not from Glinka?!

From Moscow to Belgrade, in the 1880s, the score of Glinka’s Life for the Tzar was sent from the composer’s sister Lyudmila Shestakova. According to Rahmanova, this was due to the initiative of strongly pan-slavic oriented Milij Balakirev (1837-1910). This was also a diplomatic gesture from Russia. The score was sent through Serbian embassy in Sankt Petersburg, delivered to the Serbian government. Stojan Novaković preceded the score to the National Theater of Belgrade. The fact was noted by state archives, but nobody knows what happened with Glinka’s score. Never mentioned afterwards and never performed. In fact, Glinka’s Life for the Tzar was performed in the Belgrade House of Russian Culture in 1933, but not after that score.

Supposedly Glinka’s opera was lost in the damaged National theatre during the Great War which was a great loss. If it had not been lost it could have been performed before 1914, when the modest Belgrade opera started with Verdi and Puccini. (My laments about the lost opportunity are joining the colleague’s statement that “the paths of Serbian music after Life for the Tsar [performed] in the right time, could be different!” (Pavlović 1994, 157)

As stated, Glinka was not unknown in XIX century Serbia, due again to Stevan Mokranjac who as a member of, for this occasion broadened Serbian string quartet, played violin in 1889 in the Piano Sextet of Russian Master. Afterwards, regarding presumably the shortage of suitable opera soloists, choral parts of the Glinka’s opera were sung by Belgrade Choral Society under Mokranjac, but the complete opera performed would be a natural link in the investigation of the continuity of Russian music. The link between, let us say, Bortnyansky and the Mighty Five. An important pattern for Stevan Mokranjac, as it was, it could also be a model for Petar Konjović, who before his regular studies in Prague learnt instrumentation from Carl Maria von Weber’s Freischütz. Why not from Glinka?!

Slavophilism in Coda

We see how the prevailing number of Prague students of Serbian origin was decisive in forming strong musical ties between two after World War II newly built states of Yugoslavia and Czecho-slovakia. The ground for it was definitely laid by generations born before the XX century.

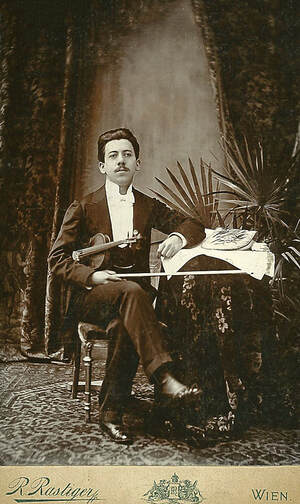

Already during the Great War, in 1916 Petar Stojanović, the Serb residing in Vienna could be flattered by Jan Kubelik’s performance in Prague of his Second violin concerto. (Mosusova 2001, 19) Later, in the interwar period the concert halls were fulfilled with Yugoslav and Serbian compositions in Prague and Belgrade, especially in late 1920. It was Miloje Milojević to be merited for many of those enterprises, his chamber music adorning Prague concert affiches (Milanović 2010 )

In Zagreb, opera director Petar Konjović was taking care of a selected Slavonic repertoire for which he has pleaded already during the Great War. This was supported by a huge wave of Russian emigrated performers in Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana.

In 1930s, in Brno and Prague was presented with tremendous success Koštana, Petar Konjović’s opera. The merit for promotion of this stage work and its exquisite interpretation was now on the side of its conductor and partly retoucher Zdenĕk Chalabala (1899-1962). It was a great surprise to read in the Czech print the ecstatic writing of Vladimir Helfert (1886-1945) about the Konjović’s Serbian Carmen.

The translated text Славенска катарза. Под утиском Коњовићеве Коштане [Slav catarsa. Under influence of Konjovic’s Kostana] was reprinted in the Belgrade musical journal Slavenska muzika [Slav Music], in 1940, numbers 7 & 8. The introductory slavophile speech by Serbian Carmen’s composer was to be read in No 1, in the same publication: Петар Коњовић, Пријатељима славенске музике. [Petar Konjovic. To friends of Slave music] in 1939. (Vasić 2014, 127, 130)

Already during the Great War, in 1916 Petar Stojanović, the Serb residing in Vienna could be flattered by Jan Kubelik’s performance in Prague of his Second violin concerto. (Mosusova 2001, 19) Later, in the interwar period the concert halls were fulfilled with Yugoslav and Serbian compositions in Prague and Belgrade, especially in late 1920. It was Miloje Milojević to be merited for many of those enterprises, his chamber music adorning Prague concert affiches (Milanović 2010 )

In Zagreb, opera director Petar Konjović was taking care of a selected Slavonic repertoire for which he has pleaded already during the Great War. This was supported by a huge wave of Russian emigrated performers in Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana.

In 1930s, in Brno and Prague was presented with tremendous success Koštana, Petar Konjović’s opera. The merit for promotion of this stage work and its exquisite interpretation was now on the side of its conductor and partly retoucher Zdenĕk Chalabala (1899-1962). It was a great surprise to read in the Czech print the ecstatic writing of Vladimir Helfert (1886-1945) about the Konjović’s Serbian Carmen.

The translated text Славенска катарза. Под утиском Коњовићеве Коштане [Slav catarsa. Under influence of Konjovic’s Kostana] was reprinted in the Belgrade musical journal Slavenska muzika [Slav Music], in 1940, numbers 7 & 8. The introductory slavophile speech by Serbian Carmen’s composer was to be read in No 1, in the same publication: Петар Коњовић, Пријатељима славенске музике. [Petar Konjovic. To friends of Slave music] in 1939. (Vasić 2014, 127, 130)

Conclusion

To conclude with the Yugoslav interwar musicology and musicography which was fully turned to music of Czechs and Slovaks also in other Serbian musical journals talking about Czeck influence on the music of Yugoslav composers, which is worth to be retrospected even to-day, referring in a new way to the omni-present Czech musicians, inhabitants of South Slavs countries of last two centuries, although in majority modest but important music workers in the Balkans.

References

|

This website is under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD