UDC: 78.02 COBISS.SR-ID 283382796 _________________

Received: Dec 25, 2019

Reviewed: Jan 22, 2020

Accepted: Feb 03, 2020

#4

Guitar Writing by Non-Guitarist Composers and Arrangers

|

Citation: Andersen, Viana. 2020. "Guitar Writing by Non-Guitarist Composers and Arrangers." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 5:4.

Acknowledgments: The current paper was carried out with the support of CNPq, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – Brasil. |

Abstract

This article describes some musical, historical and technical aspects of guitar writing carried out by non-guitarist composers and arrangers. Due to the strong influence of Heitor Villa-Lobos on professional guitar players and guitar students all over the world, and the fear from critical reviewers, as well as the consequent comparison of Lobos’ works, the Brazilian non-guitarist composers avoid to compose for guitar. The author proposed and discussed the following processes by which idiomatic writing for the guitar may be developed: 1) The harmonic analysis of the material, 2) Harmonic reduction; 3) Utilization of the open air strings principle, 4) Partnership with the interpreters. Through the given examples is presented that the guitar idiomatic writing by non guitarist composers and arrangers is quite possible and also it brings new expressive possibilities according to each composer’s or arranger’s musical personality. The imperative for the best understanding of this article exposition is to assume that the composer or arranger has specific knowledge of harmony, counterpoint, instrumentation and orchestration. The emphasis is on the study of music scores by guitarist composers and on keeping in mind that the search for new possibilities and sonorities must be always present. In the conclusion the author suggested that the development of a research method and the search for technical improvement based on the observation are crucial for both the composers and arrangers, and that they have to keep their minds always open to every musical and technical possibilities that are found in this remarkable portable instrument.

Keywords: guitar, guitarist , composers, arrangers, idiomatic guitar writing |

Introduction

Guitar, an instrument that incorporates so much of the Brazilian musical culture so well, took over the national territory as the most popular and well known instrument in the country. There is no young person who doesn’t know some elementary positions in this instrument and who isn’t able to accompany popular songs easily. However, its use in the Brazilian academic music has had some barriers since the instrument has its own technical characteristics. As a result, the Brazilian repertory at the beginning of the twentieth century is restricted to a few pieces. Thus, as it happens with percussion music, guitar music in the past century owes much, both in Brazil and abroad, to the informality of players in cafés, pubs, public squares, in short, occasions that did not call for formal “apparatus” and gala clothes.

As late as 1904, Cuban guitarist Gil Orozco performed guitar concerts in Brazil without attracting much attention from the audiences due to the low interest level concerning the instrument. Just the opposite, the piano found its way in the Brazilian homes, which might account for its wide diffusion in the country. Guitar learning was already established when Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) used the methods by Dionísio Aguado (1784-1849) for his own practices. Américo Jacomino, mostly known by the pseudonym “Canhoto” (1889-1928), can be considered the first solo guitarist in Brazil, followed by the performances of Augustín Barrios Mangore, Josefina Robledo and Isaías Sávio. Little by little they drew the attention from the critical reviewers and from the public, upgrading status of guitar from “uncommitted” to “serious”. In works of Brazilian composers is found, along with large proportion of works for orchestra, piano, voices and chamber music, a small portion of compositions for guitar, such as Lorenzo Fernandez’ (Oscar Lorenzo Fernandez, 1897-1948) Pequeno Prelúdio, and an arrangement of Velha Modinha, and Camargo Guarnieri’s (Mozart Camargo Guarnieri, 1907-1993) Ponteio, three Studies and two Valsas-choro for guitar. Maybe the titanic shadow of guitar works of Heitor Villa-Lobos – played by every professional guitar player and guitar students all over the world – and the fear from critical reviewers, as well as the consequent comparison of Lobos’ works, make all the Brazilian non-guitarist composers think twice before taking the exquisite effort to compose for guitar. However, its portability, and the easy social mobilization – all it needs is to make one contact, and the available quantity of good level interpreters – make this instrument the ideal vehicle to be used by composers and arrangers whether new or veterans. For that to accomplish it is necessary that they adapt themselves to the instrument’s language. In the following topics some possibilities and suggestions will be developed in order to get an idiomatic writing for the guitar:

For best understanding of this article exposition it is assumed that the composer or arranger has specific knowledge of harmony, counterpoint, instrumentation and orchestration. The composition material harmonic analysis

The first step to get an idiomatic writing for guitar may be initially through a macro-vision of the musical structure itself as a whole, and, in this aspect, the harmonic field enclosed in the work and its analysis play a fundamental role. Assuming that the music has already been composed for the piano, for instance, it is possible to make an analysis of the material in order to try to reach the essence of the harmonic field for future reduction into six parts – the guitar has got six open air strings that sound E1, A2, D2, G2, B2, E3, with the writing in the treble clef an octave above. The piano harmonic structure is easier than in the guitar, due to the fact that the piano player counts on ten fingers, not only four, in addition to be able to easily play any chord, which doesn’t set a limit of ten notes.

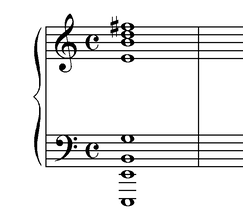

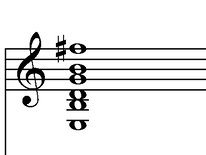

We see in the example above in the writing for piano, one chord of E minor in the root state with seventh minor and ninth major set through eight notes. It is noticed that the basic one – E – is double in the left hand and in the right hand, as well as the fifth in the chord – B. Observe that the interpretation of this chord in the piano is conditioned to playing the right hand without arpeggio and the bass, quickly leaping and reaching with the left hand the missing notes – B and G. The effect above may be achieved in the disposition of this chord with the use of some notes from the guitar loose strings, inverting some notes according to the sequential disposition of the guitar chords. The example 1.2 disposes the chord with the inversion of some notes within the chord internal range using for that the open air strings – E, D, G and B. In an reduction from piano or orchestra to guitar, the main parts that must be enhanced are the soprano and the bass voices, this may be detected in the relation between the examples 1.1 and 1.2. This is one of the analytical guiding principles that may help the composer and arranger to achieve the best sonority and idiomatic writing for the guitar. It is noticed in the example 1.2 that the resulting sonority owes little or nothing in essence to the example 1.1. Harmonic reduction

One of the main challenges of the guitar writing is in the search for this instrument expressive possibilities. The composer or arranger must try to develop, a way of reducing the harmonic field without loosing the chord “meaning”. It is not possible at first to write a ninth chord without the ninth, a seventh chord without the seventh, a sixth chord without the sixth, and so on. For instance, in a reduction from the piano to guitar or from orchestra to guitar, the less important notes in the chord, preferable the fifth or octave must be suppressed, and, as already said previously, the originality of the bass and soprano voices must be protected.

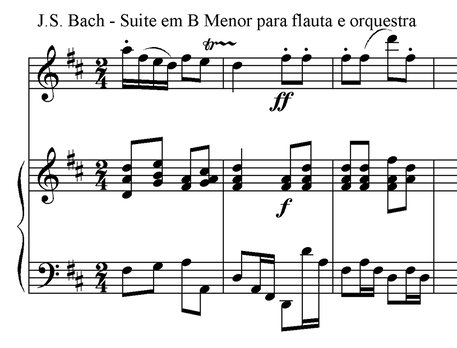

When faster passages are used this relation changes drastically. The best solution must be the reduction of the number of voices, even though for that the composer or arranger must forgot a seventh or a ninth of the chord. In this case the composer should keep the chord most characteristic notes : the root and the third in the root state in the I, V and VII grades in the scale, for instance. The same principle must be followed in the other scale grades: the most important in the tonal function. In the relation of an example to the other, it is noticed a harmonic synthesis where the chords main functions are maintained. The flute part is part of the analysis of the harmonic whole, as it completes the chords with the superior voice. In this version for flute and guitar, the main voices – the soprano and the bass – remain unaltered almost always in the same way as in Bach’s original, however the other internal voices relations are changed. Utilization of the open air strings principle

One of the great easiness of the guitar writing may be in the loose strings selective use. As a matter of fact, many of the existing pieces for guitar use widely arpeggios, scales and chords where in their construction the loose strings are structurally basic. In order to achieve this end, the composer may draw in a sheet of paper a guitar arm and write the notes, and while writing, imagine the notes that are played with the loose strings and which will be pressed with the left hand four fingers. This may be a slow process, but is one of the possibilities for learning the guitar mechanics with no need of the instrument. Another possibility is in the composer or arranger experimenting the chords and sonorous structures in loco, a process that may be slow and very much frustrating.

Partnership with the interpreters

For non guitarist composers and arrangers the guitar writing technique is at first, under some aspects, something of a mystery. The multiplicity of the effects and ways of playing the guitar – and this in the most varied guitar schools – such as: Rasgueados, harmonics, pizzicato Étouffé, Pizzicato Bartok, Glissando, Scordatura, Campanella, Tremolos, Tambora, Son Sifflè, metallic sounds, Sul tasto among other effects – make the need for the composer or arranger to find a good guitar player for demonstrations, as well as for the writing score final review. Preferably, the notation must achieve the level of idiomatic and technical notation, using precise indications of “casas”, strings, best digitations, etc. In Brazil the result of this idea is seen in numberless Brazilian productions – among these the Baião Lunar (Baião Lunar is a guitar work by this author, edited by Bèrben from Ancona-Itália, having as main partner the guitar player and professor Eva Fampas (Greece) ) – and a good example could be the partnership developed between Radamés Gnatalli, Tom Jobim and Rafael Rabelo. The German composer Hans Werner Henze summarized his partnership with the guitar player Juliam Bream and his conception concerning the contemporary language in the music for guitar:

I achieved a deeper knowledge on the guitar technique and sonorous world. I would go farther, saying that this collaboration has given me a new concept on how to write for an instrument possible to get to know, with many limitations, but also with many unexplored spaces within these limits. There is a richness of sounds able to enclose everything one would find in a great contemporary orchestra, but one must start from the silence in order to notice this: one must stop and exclude the noise completely (Dudeque 2007) Conclusion

Through this exposition we conclude that the guitar idiomatic writing by non guitarist composers and arrangers is quite possible and also brings new expressive possibilities according to each composer’s or arranger’s musical personality. To that it is the highest importance that these professionals study primarily music scores by guitarist composers and are surrounded by competent assessors in the writing for guitar for the revision work as an integral part of the composition, besides keeping in mind that the search for new possibilities and sonorities must be always present. It is not possible to have a dogmatic vision about this issue setting parameters within the popular or erudite ambits, as in a determined point both guitar schools join up – particularly in Brazil. Therefore it is useful for the composers and arrangers to keep their minds always open to every musical and technical possibilities that are found in this remarkable instrument. Maybe the maxim that guided the didactic Abel Carlevaro may help the composers and arrangers: the development of a research method and the search for technical improvement based on the observation.

References

|

This website is under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance is the publisher of Accelerando: BJMD